In our world, there is almost no silence in politics. But there are those who speak from the shadows—those who are not heard, those called the dead. We met with Maxim Evstropov, the founder of the Party of the Dead, and through him, we hear their voices: whispers, memories, protest. This is neither a joke nor a mere art experiment—it is a performance that has become politics, and politics that has turned into ritual. Maxim is not just a conductor of these voices—he also shares the music he hears himself: as if recorded on the border between worlds. This interview is an attempt to peer into that place where the boundary between the living and the dead blurs. Read and listen to what has been silenced for so long.

Maxim Evstropov — Founder of the Party of the Dead

"First Steps Through the Dust"— What moment served as the starting point for creating the Party of the Dead: personal experience, political disillusionment, or the call of those who go unheard?

— The party has many starting points—there’s always more than one. But perhaps one of the most obvious points of departure is the abuse of the dead in politics. This is very characteristic of the political realities in the Russian Federation. Of course, this happens elsewhere, but in Russia, it reaches its most grotesque expression. The Party of the Dead arose largely as a reaction to this exploitation.

By 2017, when the party appeared, political reality in the RF seemed very strange to me: the border between the living and the dead was seemingly erased, yet no one was truly living: everything happened as if in a haze of the undead, death-in-life, life-death. One day, dead voters cast ballots for a convenient candidate; the next, a dead deputy votes for a convenient law; then someone proposes granting the dead the right to vote so they can be used to vote for the “right” person without any pretense. The dead are forced into a hellish can-can, while the living are treated as if they are already dead.

I watched the rise of the “Immortal Regiment” with particular horror.

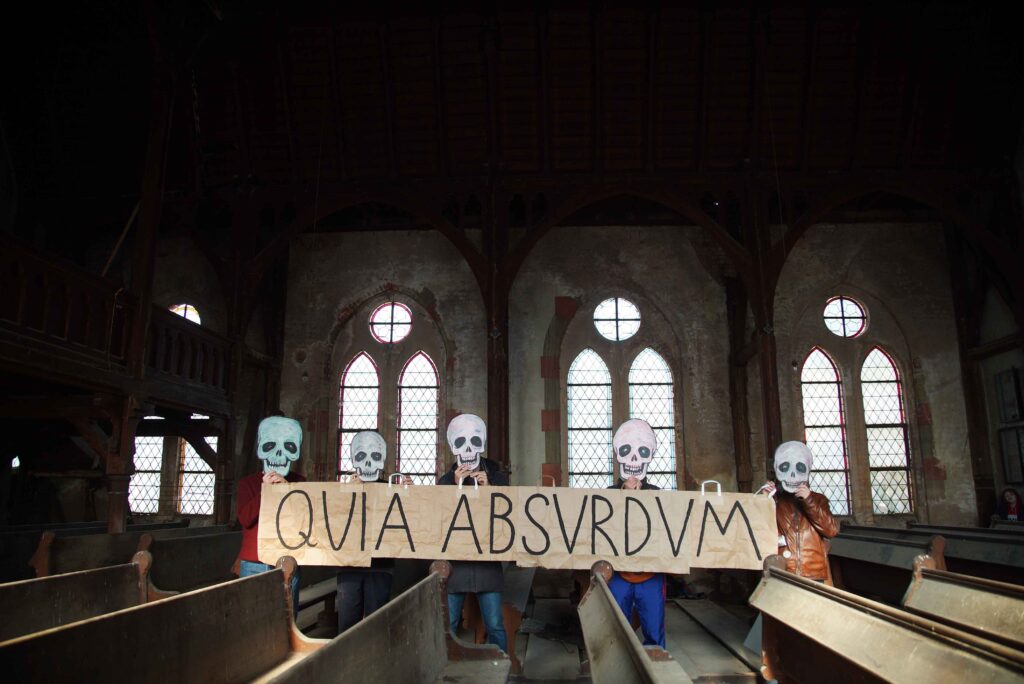

I saw the very beginning while I was still living in Tomsk. It seemed like a decent grassroots initiative for commemoration—but something about it was wrong. I couldn’t shake the feeling that they were dragging the dead into the streets thoughtlessly, with a kind of indifference. The “Immortal Regiment” seemed to open a sluice to the underworld, from which the chthonic monster of war eventually emerged—a political “non-corpse” (to use the term of the necrorealists). Many of the party’s early actions and demonstrations were parodies of the Immortal Regiment.

Additionally, the Party of the Dead did not arise from a void, but from the diverse practices of the performance group {rodina}, which engaged in “experimental political art.” We had quite a lot focused on death and necropolitics. Besides, I had long wanted to make activism and protest art more “gothic” (something more gothic than heroic).

— What do you invest in the word “dead”—is it a metaphor, a political category, or a concrete community?

— First of all, it is not a metaphor: the dead are any dead, truly dead. This is the fundamental meaning we start from—and then various figurative meanings can be layered on top, like the “dead while living,” political corpses, etc. But the dead, the truly dead, remain the base for all these metaphors—because there are more dead than living. Paradoxically, the dead are the largest social group. And life, as I see it, is a special case of a more universal non-living state.

— How would you explain the Party of the Dead to someone who hears the name for the first time and thinks it’s a joke?

— First, I would probably reassure them as best I could that it’s not a joke. Broadly speaking, the Party of the Dead is a party that includes all the dead, as well as those living who feel the need to stand in solidarity with the dead. Since this party includes all the dead—the largest social group—it is, effectively, the largest party in the world. But it can hardly exist officially, as the dead do not recognize any state, and they, in turn, do not need recognition from any state.

Furthermore, the dead are not only the largest social group but also the most marginalized and disenfranchised: “the largest people, the smallest.” It is, in essence, a necro-proletariat: on one hand, they are maximally excluded; on the other, the living exploit them constantly in almost everything, not expecting the dead to respond. The Party of the Dead represents precisely that response.

“Echo of the Forgotten”

— Does the Party of the Dead have a program—or is the absence of a program its political position?

The Party of the Dead is an entirely impossible party, and its program is equally impossible. We define our common goal as necro-revolution, and three tasks lead toward it:

1. To ensure the dead speak—by themselves and on their own behalf, not as resurrected beings, but as the dead.

2. To question the claims of the living to speak on behalf of the dead.

3. To remind the dead that they are dead.

The first task seems completely impossible, the third—strange, though it is essentially a “memento mori” for the dead—because many act as if they don’t know they are already dead (this applies to the living as potential dead as well). The second task—the critical one—seems the most realistic, though it too is problematic.

Many living people love to speak for the dead, claiming privileged access to them. The dead become a resource for their own authority. Putin, for example, tries to frame things as if he isn’t just a pathetic KGB man who happened into power, but that behind him stand especially valuable dead (like WWII veterans). Limonov also filled his party of the dead with choice cadres, creating a sort of pantheon of heroes. But, firstly, all dead are equal—because none are “deader” than others. Secondly, no one has a primary right to speak for the dead—since all the living are in roughly the same state of non-knowledge regarding them.

The living don’t just misappropriate the voices of the dead; they force them to say things convenient for themselves. Very often, the living put fascist nonsense into the mouths of the dead: thus the dead begin to protect “traditions” and “centuries-old foundations” and seemingly sanction wretched dictators with their magical authority.

But we ourselves speak on behalf of the dead: we are forced to speak for them, because even to criticize the claims of those who speak for the dead, one must speak on their behalf. We do not hide this fact—though, of course, it does not justify us. So everything we do remains under a great question mark.

Whatever the case, we try to adhere to a certain “logic of death” and draw political conclusions from it. This logic, we believe, is equally accessible to everyone.

This logic is nihilistic, anarchic, and communistic.

Death is not another world, but the absence of world (and in this sense, it is nihilistic).

Death is the maximum contempt for hierarchies, a radical horizontal (and in this sense, it is anarchic).

Death is the base, the most common thing everyone has (and in this regard, it is communistic).

Regarding the authority of the dead: yes, historically it is one of the sources of political power (which is always “power of the dead” in that sense). However, using the dead as a resource for authority is always abuse and contains a trick. The dead have no power, and their authority is a self-destructing authority.

— What problems of modern society do the dead see better than the living, in your opinion?

— The ancient philosopher Parmenides attributed a negative sensitivity to the dead: if the living are sensitive to heat and light, the dead feel cold and darkness. I am also inclined to attribute a kind of negative political sensitivity to the dead: the dead are maximally sensitive to violence, inequality, and exclusion. Therefore, in general, they “see” any political problems better than the living (“seeing without seeing,” or something like that).

— How do you imagine the participation of the dead in the political process—is it voice, memory, protest, silence?

— The dead are somehow always already participating in the political process, as they are in the past, which exists as a trace or a testament. The dead are in culture, in institutions created by those no longer living. The dead are in the language the living speak. And the specter of communism is still wandering somewhere, long ago moving beyond Europe. In our practices, we try to show that the dead belong not only to a finished, “convenient” past but also to the future. The dead “are present” in our now as the future.

Regarding silence and the voice of the dead, I’ve long had a strange idea. At first glance, the voice of the dead seems the most unheard thing possible. It feels as if they are mute or that their speeches—like a faint rustle—are always drowned out by the loud-mouthed living. But the dead are by no means silent; moreover, they all speak everything at once. Their speech coincides with their language (in the structural linguistic sense). This monstrous noise is what constitutes silence for us—because billions of voices sounding “simultaneously” are beyond the perception of the living. To exist is to shield oneself from this deafening silence.

— What elements of performance or art are built into your party’s activities by design?

— All of this is too insane to stay within the boundaries of politics, so it moves into the realm of art, where such things are seemingly permissible. Nevertheless, it remains a political demand—and therefore cannot be “just art” confined to museums and galleries.

— Why do you think the idea of the Party of the Dead is relevant now, rather than ten or twenty years ago?

— What is happening now is a kind of flowering of necropolitics, though not yet its peak. In any case, what we talked about five or more years ago is becoming hard to ignore. This isn’t just about Russia. But in Russia, there is a literal “death conveyor”: war for war’s sake, a “special operation” death-economy (where it’s more profitable to go kill and die than to live), a resource-based attitude toward everything—and Putin, obsessed with preserving his own life, almost with the idea of physical immortality.

But broadly speaking, the Party of the Dead would always have been appropriate. It’s worth noting our party isn’t even the first in the post-Soviet space. In 1998, a “party of the dead” appeared in Latvian National Bolshevik circles; in 2011, artist Lena Hades founded her own. In a way, the party of the dead has always been there—even when nothing was there yet.

“Voice of the Shadow”

— The dead have rights — What are rights for the dead?

— It is problematic to speak of human rights in relation to the dead. The rights to life, labor, rest, and education are suspended. The right to freedom of movement or religion too—though the more abstract “right to freedom” is more interesting. But there remains a right common to both the living and the dead.

I would formulate it as the right to justice. Justice must be served toward the dead as well—otherwise, it isn’t justice at all.

— At what point does a person enter your electorate: at biological death, social death, or even earlier?

— People join our party, primarily, with “true” (biological) death, which will happen sooner or later. This possibility is open to everyone; thus, everyone is potentially a member. In a sense, everyone is already in it, as the living is a special case of the dead.

— Can a living person join the Party of the Dead, and what does it require of them—besides the desire?

— Yes, the living can join while still alive. For them, membership is voluntary, unlike the dead, for whom it is necessary. To fully participate in party life, one should also stand in solidarity with party principles (freedom, equality, mortality).

“Crossroads of Timelessness”

— How do you maintain the boundary between a political project and an artistic statement, or is that boundary unnecessary for you?

— What we do is located exactly on that boundary. It’s not that it’s unnecessary—rather, we constantly question it. It’s not about the aestheticization of politics, or even the politicization of aesthetics, but a constant crossing of this border. And this applies not only to the general boundary between politics and art but to the limits of the aesthetic and political in general.

— What reactions do you hear most from people—laughter, fear, interest, misunderstanding?

— We encounter all four types. But generally, what we do seems terribly funny to me. However, the tragic component should not be forgotten either.

— What real social or political processes do the dead catch earlier than the living—and how does this knowledge change your actions in the world?

— The dead generally catch the future “earlier” because they are closer to it.

“Call of the Empty Halls”

— If the Party of the Dead were to get a seat in parliament, what would be its first gesture, its first intervention in the life of the country?

— Depends on the country, of course. But if it were Russia, the first gestures—obvious not only to us—would be the withdrawal of troops from Ukraine, the release of prisoners, and amnesty for political prisoners. Beyond that, according to our tasks: toward global necro-revolution and the withering away of all states.

— How do you organize your work: are there meetings, documents, a charter—or does the party live by the laws of another world?

— We have a draft charter, which remains a draft because its ratification requires confirmation from all the dead. We love documents too: we issue party IDs to anyone interested, which are considered real in any case—even if they are fake. Meetings happen too. While in Russia, we often met in cemeteries. We once held a congress in Georgia.

— With which modern political or artistic movements do you feel kinship, and with which a fundamental divergence?

— As activists, we often interact with other libertarian movements: queer, fem, eco, vegan, left and anarchist, decolonizers. We clearly have nothing in common with state-worshippers and fascists.

Personally, I like different strange things: libertarian Satanism, magical Marxism, or Mark Fisher’s “Gothic Communism.” I’ve always been drawn to “dark” aesthetics. Yet, mainstream activism usually ignores it, while “darkness lovers” are mostly “non-political” or simply fascists. I am trying to create a strange synthesis that satisfies me.

“Memory of Forgotten Voices”

— How do you feel about attempts to perceive your party as satire—does it help or hinder?

— We view it with understanding. Death is funny and strange.

— If the dead are memory, trauma, and forgotten stories, what kind of memory are you trying to return to the political field?

— Memory of the future, primarily. And also memory of that which left no trace.

— What political task, in your opinion, can only the Party of the Dead perform and no one else?

— The task of preparing for the global necro-revolution, obviously.

“Silence Remains”

[remains]

I so love partitions

they are our manner, our habit, our dull freedom

and waste

or else to love so

what remains after the dissolution of partitions

that dull sea

for in any case it remains

remains

to listen into this “remains”

into its not even splash

not even hum

remains

when everything else disappears

(our manners, our habits, our dull freedom

and waste)

[30/7/2011]