This time we have something exotic — photographs taken in modern-day Minsk. We continue to introduce you to photographers, and today we present the work of Hanna Shchebetova. We invite you to see the city through the prism of her art and read our conversation about how Hanna interacts with reality and finds her subjects.

Inner Mongolia in the Commuter Towns

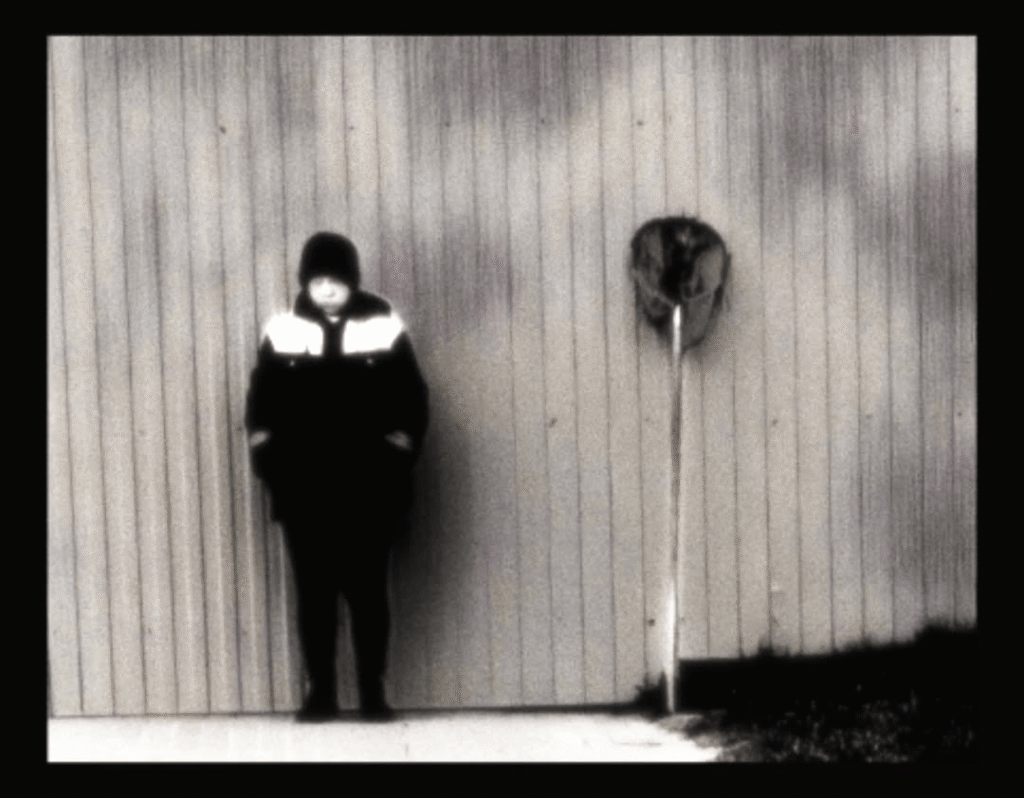

— In Belarus, everyday beauty is often intertwined with the grayness of prefab panel blocks and the hopelessness of residential districts. How do you find “that specific shot” where an ordinary passerby sees only depression and cracked asphalt?

— If a person sees depression and a crack in the asphalt, that’s already a victory. It means that objects or abstract states are catching their attention. They are reflecting; they are seeing. Essentially, they are already a potential photographer.

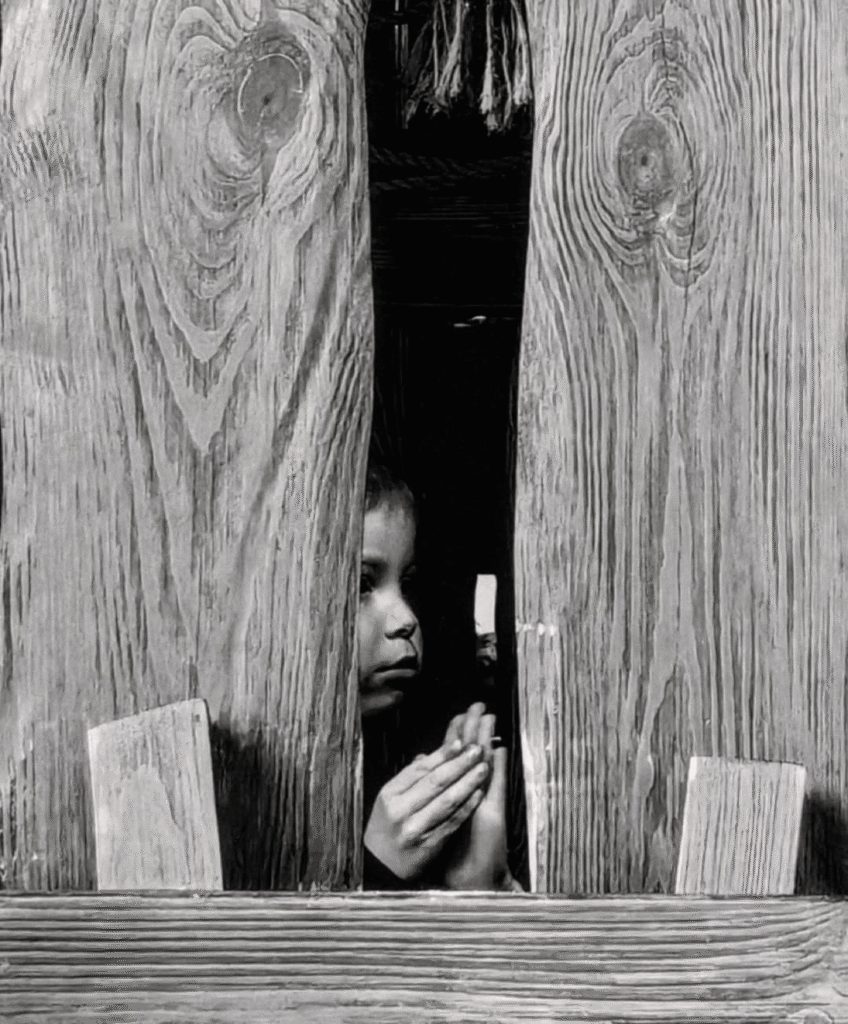

For me, photography is a way to avoid being detached from the world, a way not to be blind or submerged in a somnambulistic state. I also see the cracks and the depression, but sometimes I see happiness and “non-cracks.” The main thing here is not what you see, but the process of seeing itself.

— What lies at the core of your vision?

— It’s a great mystery. It is an exploration. I can only guess why I like one thing or another, and I don’t want to give definitive answers, as that would mean subscribing to a specific ideology.

— For decades, we were fed polished images. Why do a broken cup or an old floral curtain evoke more emotion today than a perfect studio portrait?

— Any mass-replication of images eventually turns into aggression and intrusion. This causes rejection and a desire to see something opposite. We live in a world overrun by simulacra broadcasting “perfection,” which is why these “jagged” images touch us. We have a direct experience of interacting with them—reality is never perfect. Right now, the pendulum has swung toward texture, but it’s possible that in time, “polished” images will become the tool of counter-culture.

— Is there a difference between the light in a Khrushchev-era flat in Chizhovka and the light in a trendy coffee shop? Where is there more truth for you?

— In our cultural code, natural grayish light is often elevated as a symbol of truth. But for me, there is no difference. Both in a prefab block and in a coffee shop, you can catch a moment that creates a breach in the fabric of perception and reveals another world. It doesn’t depend on the location or the type of lighting.

Hunting for Masks

— Street photography in Belarus is always a bit about aggression and espionage. How do you choose your subjects in a crowd?

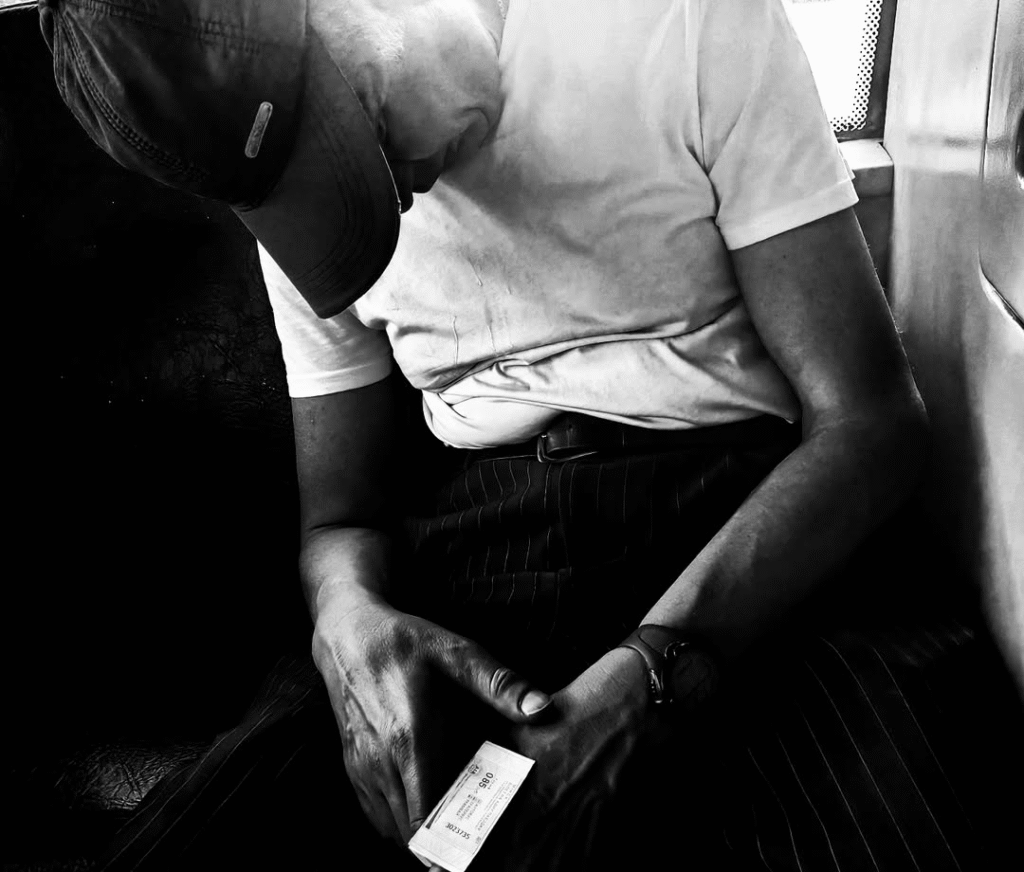

— A hunting instinct kicks in. I might not even realize what exactly I’ve seen, but my attention concentrates instantly. My heart rate quickens, cortisol and adrenaline are released—I need to run and “grab” that shot. In this metaphysical food chain, I am a predator attracted to a specific type of “prey.”

— And who are your heroes: those who are more integrated into the architectural grayness, or the “system errors”?

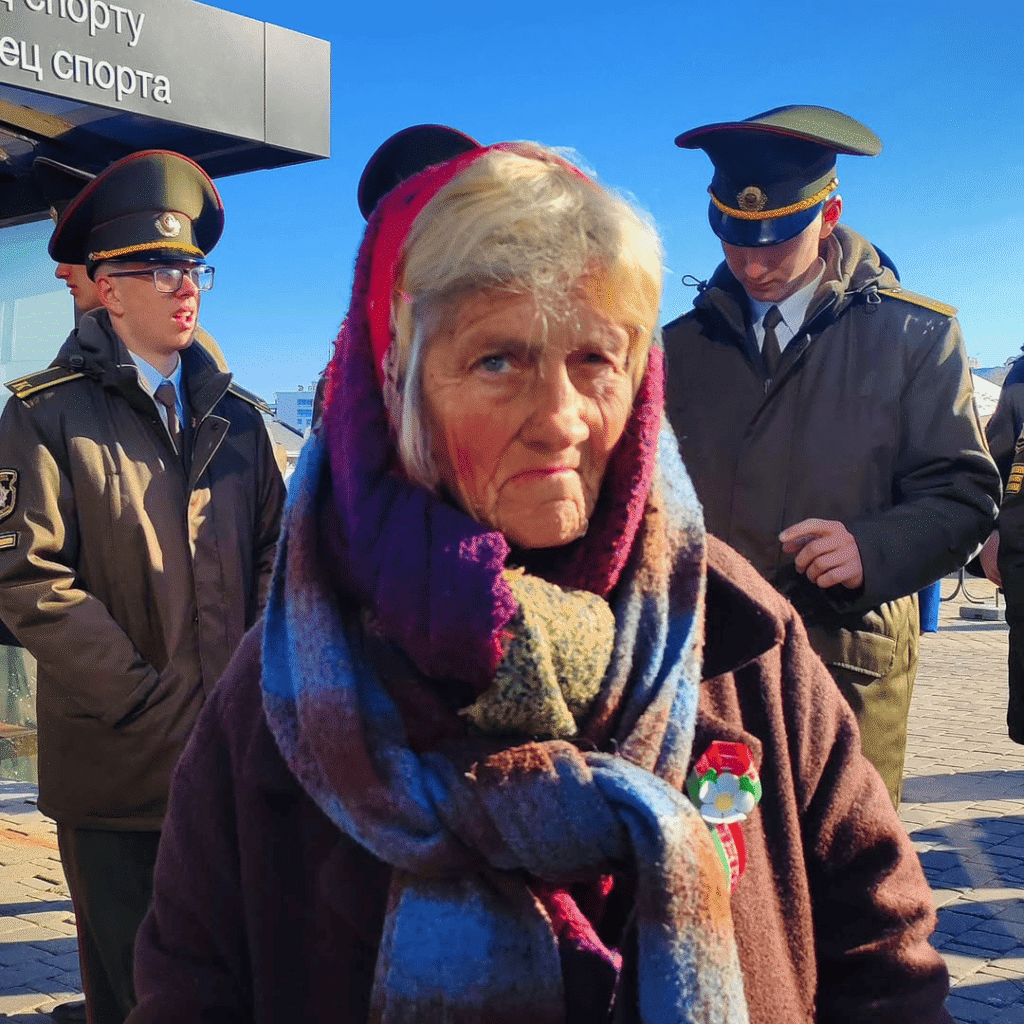

— This question touches on two types of ideal heroes: those who stand out completely, and those who fit in perfectly. Everything in the middle is boring; it simply blends into the background.

In our environment, people in workwear—street cleaners, the “little green men”—blend in perfectly. Or the bureaucratic ladies with beehive hair and high heels. But it’s precisely their organic fit that raises the most questions. How can someone merge so thoroughly with the system? Who are they on their own? Do they even exist outside of this role?

For those who stand out, the questions are different: how did you end up like this in this environment? How did you manage to preserve yourself? What paths did you take to become objects that absolutely contradict everything around you? Both are truly fascinating.

— A portrait is a deal between who we are and who we want to seem. How do you uncover that domestic sincerity in passersby?

— I don’t take staged portraits. Мои кадры are like the click of a shutter that sounds like a gunshot. The people in the frame are either being themselves or are startled by the fact they’re being photographed. Everyone wears a mask designed for specific distances. When a person walks down the street, their mask is simple: “I’m fine, I’m going about my business.” If you get closer, the image becomes more complex. I try to shoot so that people don’t see me—that way their mask remains the one they use to interact with the world from a distance.

Shamanism in a Drawer

— Let’s talk about objects. What detail in an ordinary Belarusian interior do you “criminally ignore”?

— I don’t know if such a concept as a “Belarusian interior” even exists. Most of life now happens in screens. We create our own “virtual inner Mongolias” there, and everything that remains outside the smartphone is the very interior we’ve stopped noticing.

Grandmother’s lace doilies on tea sets are artifacts of the past, a museum-like post-Soviet code. We ignore modern everyday life not because it lacks beautiful objects, but because our attention is turned inward.

Interest in an object isn’t inherent in the object itself—it’s born in the moment our perception interacts with the external environment. Some ordinary drawer can become incredibly beautiful for a fraction of a second, and then turn back into junk. You can, of course, try to break the automatism of vision intentionally: walk on your hands or climb onto a table to see the room differently. Но для меня это выглядит надуманным. What’s far more important is an inner readiness for any object you touch every day to suddenly appear as something new to you.

— What is the ugliest thing in your apartment that is actually a masterpiece, or just junk you can’t bring yourself to throw away?

— I have an old pair of my ex’s underwear that I still wear. It’s a very ugly thing, in my opinion, but I can’t throw it away for some reason. Also, I live with two Madagascar cockroaches—Stalker and Sitr.

— And one last question. What is the beauty of a moment in three words?

— It’s the decisive moment.

Photo by Hanna Shchebetova