In Warsaw, amidst bustling bars and apartment concerts, music resonates that intertwines Balkan gloom, punk energy, and Belarusian reflection. “Serbian Knife” (Serbski Nož) is a band of Belarusians in exile whose lyrics speak of violence, faith, and human nature. They play at the intersection of post-punk and post-hardcore, but for them, music isn’t about genres—it’s a way to make sense of lived experience, their own and others’ boundaries, and the nature of good and evil. Read the interview with “Serbian Knife.”

How “Serbian Knife” was born and what it means to its members

Hi! How did the name “Serbian Knife” come about?

M: We get asked about this in almost every interview—and almost always as the first question. I think it’s only fair to address it to Sergey. Sergey Alekseevich, the floor is yours.

S: Well, in short, back when we were working in Kyiv, we often came up with things like this. At the time, I was interested in the history of the Balkan Wars and was struck by how brutal they were. An image emerged in my mind, symbolizing senseless ethnic violence and human hatred in general. That’s how the name was born.

M: For me personally, it is also a symbol of senseless cruelty and violence. At one point, I was fascinated not so much by history as by “Balkan cinema”—they reflect on the same themes: war, violence, destruction. And I want to emphasize: “Serbian Knife” is not the same thing as a “Srbosjek.”

S: Yes, a “Srbosjek” is a real weapon used by Croatian Nazis to kill Serbs. It was attached to a glove, allowing for palm strikes without letting go of a weapon in the other hand. But our name is not connected to that.

St: To me, it’s not even so much a symbol of human cruelty as a reflection of human nature itself—our tendency toward decay and baseness.

M: Another association I have with the Balkans is that the wars and outbreaks of violence that occurred in Eastern Europe and the countries of the former USSR manifested with a particularly high concentration in the Balkans. After the fall of the socialist bloc, everything flared up there almost immediately—and with an enormous degree of cruelty. They weren’t called the “powder keg of Europe” for nothing.

Musical influences and creative atmosphere

What kind of music did you listen to as a teenager?

St: I suppose I’m still a teenager in some sense. But if we’re talking about my early years—I just listened to rock: Rammstein, Lyapis Trubetskoy. Later, I discovered modern youth music—LSP, Max Korzh, the 2017 wave. Then I arrived at more interesting genres: indie, classic rock, abstract rap. I was particularly influenced by the band “Molodezh vybirayet kosmos” (Youth Chooses Space)—a mix of abstract rap and heavy guitar parts.

My introduction to the Belarusian scene started at the “Epofest” festival in Vitebsk. I saw the band “Trup” (Corpse) there and realized that there is a living alternative and punk scene in Belarus. Since then, I started digging deeper, studying the history of the scene, even while already living in Poland.

The biggest influences on me were abstract hip-hop in the vein of Makulatura and the British/American shoegaze scene—Slowdive, My Bloody Valentine—as well as punk bands. And yes, as a child, I loved Siberian rock for its DIY approach: music recorded in a basement on a cassette tape, without pretension—just like modern rap. This inspired me to try making something of my own.

M: My path was similar. As a teenager, I listened to popular music and rock without strict genre boundaries. In high school, I started gravitating toward heavy music: thrash metal, early death metal. At university, I met Seryozha, and he introduced me to punk rock and post-punk. Petlya Pristastiya became my favorite band; I went to their concerts and followed their releases.

In parallel, I listened to Dead Kennedys, the Russian band PTVP, and Khimera. There were also periods of obsession with hip-hop, but unlike Stas, I’m not a fan of Makulatura. I’m closer to “Moy bumazhnyy paket” (My Paper Bag)—their lyrics are a bit more philosophical. The influences on “Serbian Knife” were punk rock, post-punk, and post-hardcore in the vein of Fugazi.

S: I started with American pop-punk—Sum 41, Blink-182. Thanks to them, I learned to play guitar. Then I started studying the roots of the genre and immersed myself in 80s punk and hardcore: Black Flag, Fugazi, Bad Religion.

D: And I listened to Russian rap. I ended up with the guys as a punk drummer. Punk is easy to play, so I didn’t need much musical training.

Your tracks are filled with atmosphere and dark imagery. Is this a reflection of an internal state or a deliberate artistic device? Could it be said that you are gloomy people?

S: We probably shouldn’t be called gloomy people. It’s more of an unconscious choice. I don’t really believe that creativity can be 100% deliberate: it always happens half-subconsciously, half in a state of a semi-trance—semi-consciously. Personally, I’m not a gloomy person; I’m rather melancholic by nature. And the lyrics are, again, an attempt to process what happened to us, what happened in the region, and what happened in our specific lives. It’s a reflection on what a human being is and how human nature is structured.

St: I’ll tell you a related story regarding “gloominess.” Before I met Sergey, he had a musical project with an Instagram account full of pictures. Living here, I was following it and occasionally saw the stories. For some reason, I developed a subconscious (well, okay—not subconscious, but quite specific) feeling related to those images. At one point, I see a story—a photo from a bus window—and based on the landscape, I realize it’s my neighborhood in Warsaw. Then the next story: some room, tiles on the walls, unclear what kind of place it is. And even before we met, I suddenly got the impression that Sergey worked at the psychiatric hospital near my house. I decided the photo was from there: first, a landscape literally opposite my house, then this strange room with tiles. I thought, “Aha, there it is, the darkness.” Later, it turned out it was just a kitchen.

M: I would add that I completely agree with the guys: we are definitely not gloomy people. At a concert, obviously, that impression might be formed within the framework of a stage persona. But when we’re just standing at the bar or down in front of the stage, we are normal: sometimes cheerful, sometimes, I admit, tedious.

D: I agree with Misha one hundred percent.

Good. Next question. Many of your songs contain religious and philosophical references. What role do philosophy and religion play in your work?

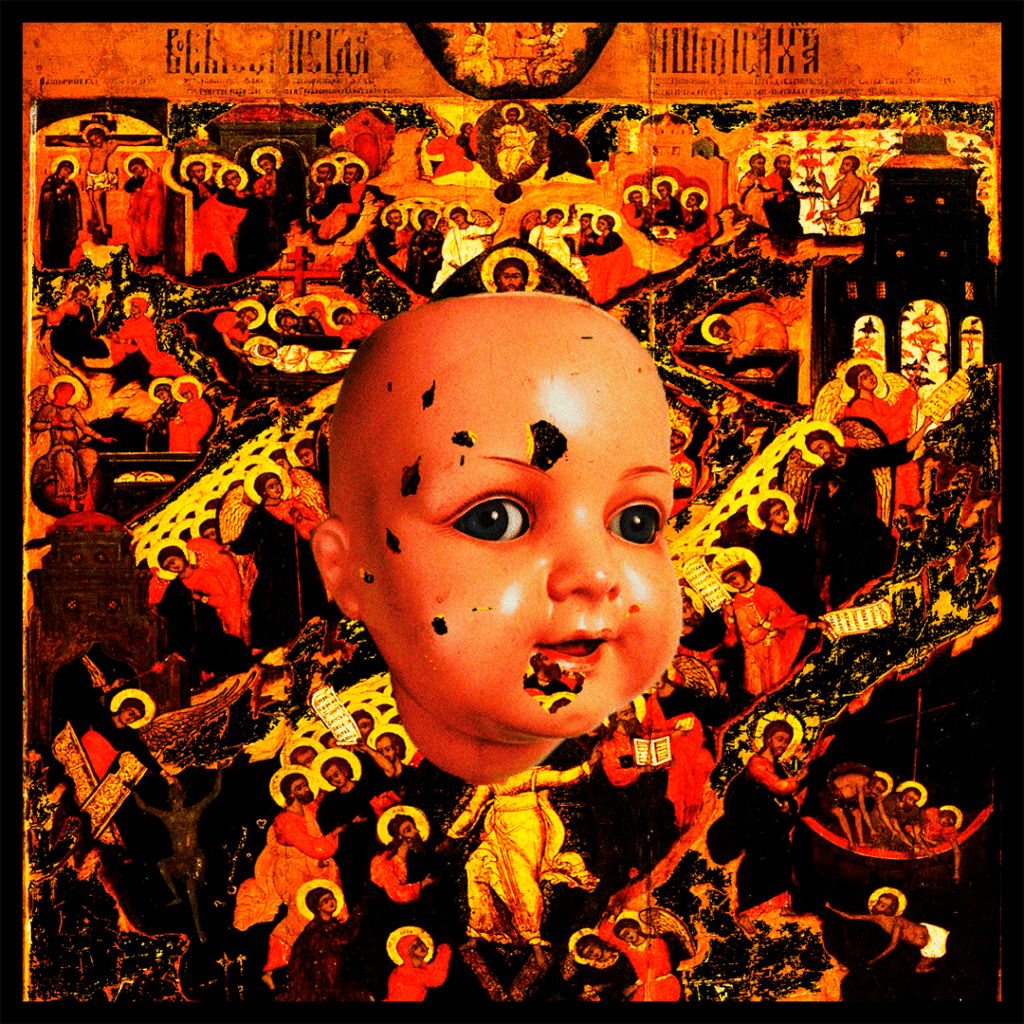

St: It seems to me the answer already partially lies in Sergey’s previous words: lyrics are born unconsciously from what is inside. Therefore, it is connected specifically to personal religious experiences and discoveries—rather than just an attempt to deliberately “take and work” with a religious theme. Apparently, it gathers inside like that and then comes out on its own—everywhere, in lyrics, in imagery. As for the role, much depends on what we call religion and how we understand it. Speaking for myself: I consider myself a Christian, and for me, this plays a fundamental role in life.

Are you all religious people or not?

M: I would call myself non-religious. It seems to me I don’t do enough to categorize myself under any religion—I don’t engage in anything of the sort and cannot honestly count myself as such.

S: It’s important what exactly is meant when the question about religion is asked: is it an attempt to reinterpret a more historical, more abstract experience—or is it a personal experience? For me, everything began with an interest in religion as a phenomenon: historical, cultural—well, let’s say philosophical, structured, and abstract. Something that shaped traditions, influenced surroundings, etc. And then, as life goes on, you realize: everything superfluous peels away—and only what you have experienced yourself, what you have personally felt and understood, remains. That is how I came to faith: through a personal transformation of views and opinions. For myself, I found a perspective on reality that matches my experience. I’ll put it this way: my identity as a “Christian” is one of the foundational ones; it prevails over national, political, etc. At the same time, I am closer to the spirit of Protestantism: I find large organized religious institutions—Orthodox or Catholic—alien. I believe they have little in common with Christianity as faith and as a personal experience.

D: Religious. Without fanaticism—I suppose that’s how I’d put it.