Maksim has managed to live in various corners of the world: from Belarus to Asia. During his travels, he seals the moments that surround him: urban landscapes, noisy streets, and the residents of megapolises. About how important color is in photography, about fear, anxiety, and emigration — read more in this new article from the “Art in Emigration” series.

Maksim, photographer

— What inspired you to start practicing photography and urban landscape photography specifically?

— I actually started with portraits of people I knew and strangers. I even planned to make a living from it, but because I left Belarus to study, I dropped the whole thing. Later, I accidentally started shooting streets; it happened simply: there were no people around, but I had a camera and time, there was the street, and everything converged into one.

Photo from Maksim’s personal archive

— How do you choose the locations for your shoots? Do you have favorite cities or districts?

— I don’t have particularly favorite places; wherever I end up, I shoot. But, of course, it’s good when you know the city at least a little: where the contrasts, characters, and stories are, or some colorful local things. In general, I don’t “choose” at all; I just love to walk. In emigration or travel, many of your usual activities fall away, so I replace them with aimless walks with a camera.

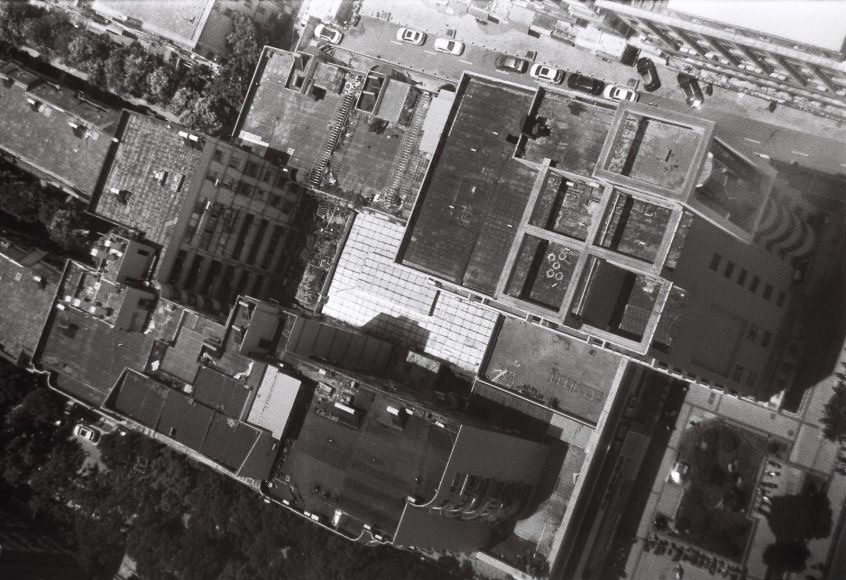

— What architectural styles or elements most often catch your attention?

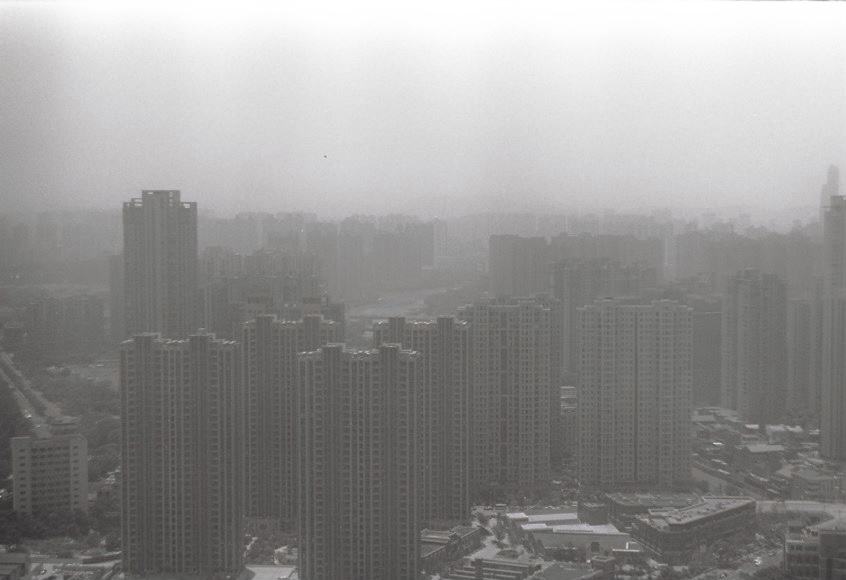

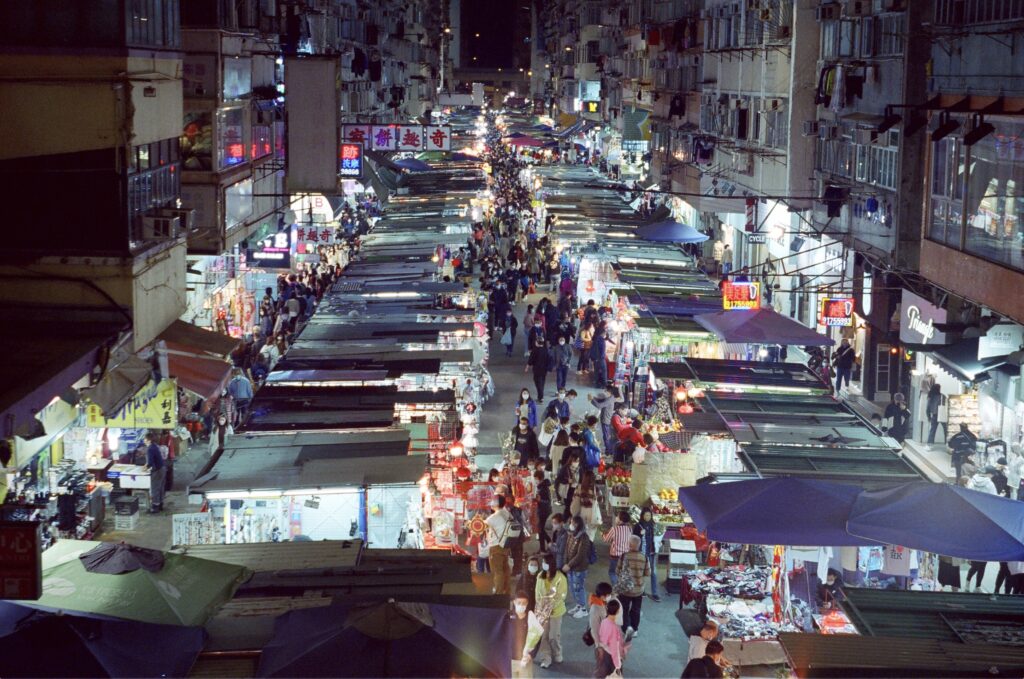

— Mostly the 20th century: modernism, brutalism, constructivism. But really anything, from ancient temples to office glass boxes in Asia — those dystopian landscapes, cyberpunk.

— What role do light and shadow play in your photographs?

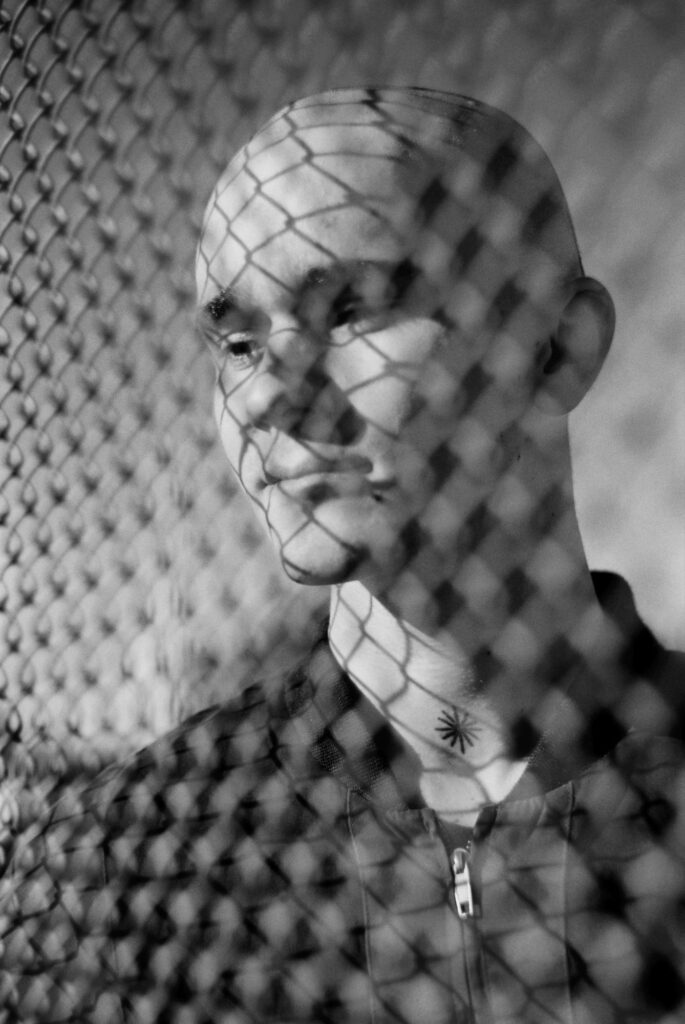

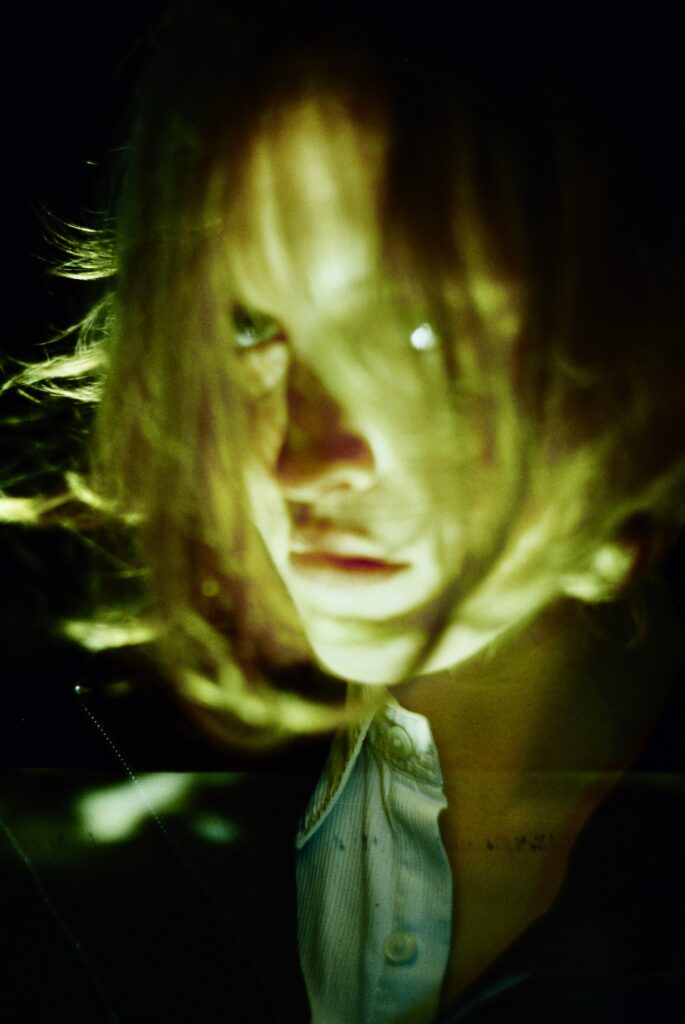

— I started by measuring everything, almost making sketches of the shots. It was important for me to think through the locations, the pose, some kind of story, but in reality, good shots come out on their own. When you act according to a preconceived plan, it becomes staging and posing; it almost never looks natural, and for me, it stops being a footprint of reality. Regarding light, I am usually drawn to deep, high-contrast photos.

— What role do people play in your photographs of urban landscapes?

— A big one. They are my characters; I like photographing people.

— What difficulties do you encounter when shooting in an urban environment and how do you overcome them?

— Catching the moment, but perhaps it’s harder to overcome shyness and confidently intrude into personal space; people always react differently. Though I have almost never encountered aggression, violating personal space is the hardest thing for me.

— How do you think urban photography can affect the perception of a city by its residents?

— Of course it can; for example, how Soviet planned development is perceived by most people today compared to its early photographs. But what is far more interesting, of course, is not propaganda, but the artist’s vision of specific places at specific times. I would call my photographs documentary rather than urban, although there are landscapes too.

— What changes in urban architecture or planning would you like to see in the future?

— You can take Berlin as an example here. Although many consider it unattractive, some urban details remain untouched for a century. For instance, lamp posts, lanterns, the subway, ironwork—even the trains in the metro can look the same. And it’s very cool when a city preserves its visual code even while adding new elements.

Photo from Maksim’s personal archive

— How do you see the connection between urban or documentary photography and the social problems of a city?

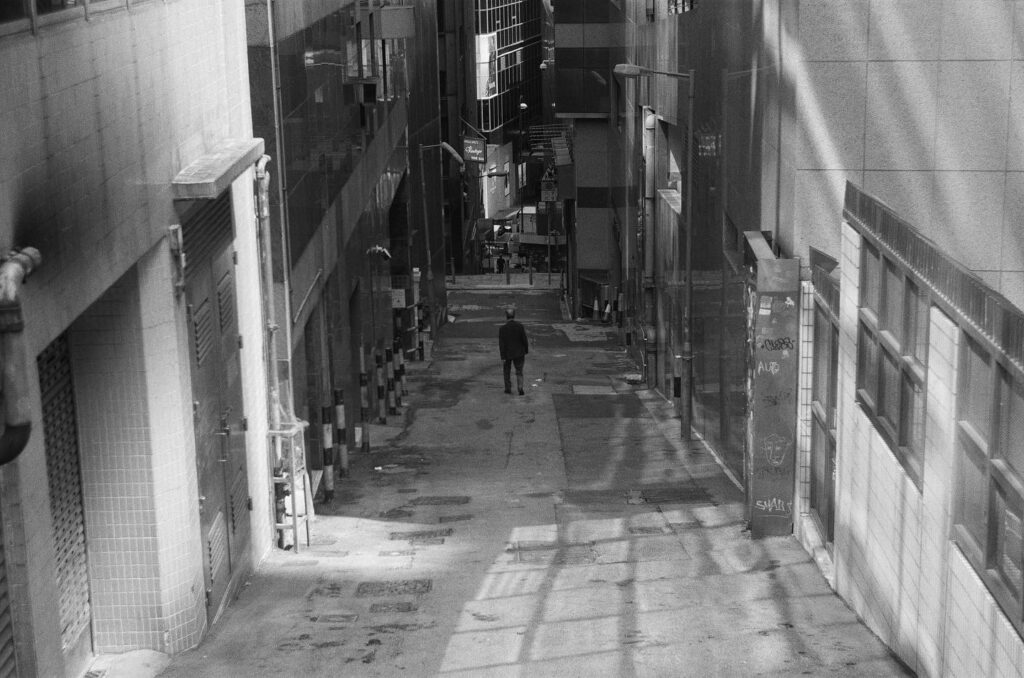

— In my works, I see a mirror of myself. It doesn’t matter what I was photographing; I remember what I felt at that moment looking at the photo. Anxiety and fear, or something else. People in my shots often feel not very comfortable, especially in street photography. What I mean to say is that, somewhat unconsciously, I capture what reflects me.

— You mentioned fear and anxiety? Where do they originate in your works?

— I think it’s a reflection of my alienation in society and an inability to find my place even in a large city.

— Which projects or photographs do you consider your most successful or significant?

— Overall, I don’t consider myself an established photographer. But I was proud of myself when I developed several rolls of film from Hong Kong with blurry night shots. I felt that I had found something new for myself, a new self-expression.

— Which places or cities would you like to photograph and why?

— Something non-trivial: India, Africa, maybe Japan. I feel that the further away you go, the easier it is. When you are in an unfamiliar place, you pay more attention to mundane things and it’s easier to pick out something significant among them. I explore culture or social aspects in photography more unconsciously. Shooting for me is more of a photo diary, where you capture a state of being rather than just moments. When you look at the photo, you likely won’t remember where you were going, what the plans were, or what you were thinking, but there is an imprint of your state of mind.

— What role does color play in your works?

— I don’t really feel much inspiration in color photography, except, of course, for nocturnal Asia, Wong Kar-wai and all that. But in general, black and white film is all that’s needed from everything invented in photography.

Photo from Maksim’s personal archive

— Are there books, films, or other photographers who have had the greatest influence on your work?

— My mentor from an early age is Pavel Bulva. Regarding photographers, I am super uneducated and bad at remembering names. There is a photojournalist from Canada named Greg Girard who is very cool. He went to Hong Kong for the first time at 18 and has taken many photos of it since then. I really like his photography style, but my vision was influenced more by cinema. I really like Bergman’s framing. Or Melville and his millimeter-precise storyboarding; it’s very pleasing to watch.

— If photography were music, what kind of music would come out of your photographs?

— I think it’s very cliché: Neil Young’s soundtrack for Jim Jarmusch’s “Dead Man,” or Dirty Beaches, or Miles Davis, possibly Swans.