New Year is a time for fireworks, festive tables, and so on. But as we all know, far from everyone can spend this day with friends and loved ones. Nottoday has decided once again — and in such matters, there is no such thing as too many reminders — to draw attention to those spending the New Year in places of detention.

In this material, together with Dissidentby, we try to understand what the pardons of Belarusian political prisoners in 2025 meant, what stands behind these decisions, and how the Lukashenko regime is looking for new ways to earn gain points favor with European countries.

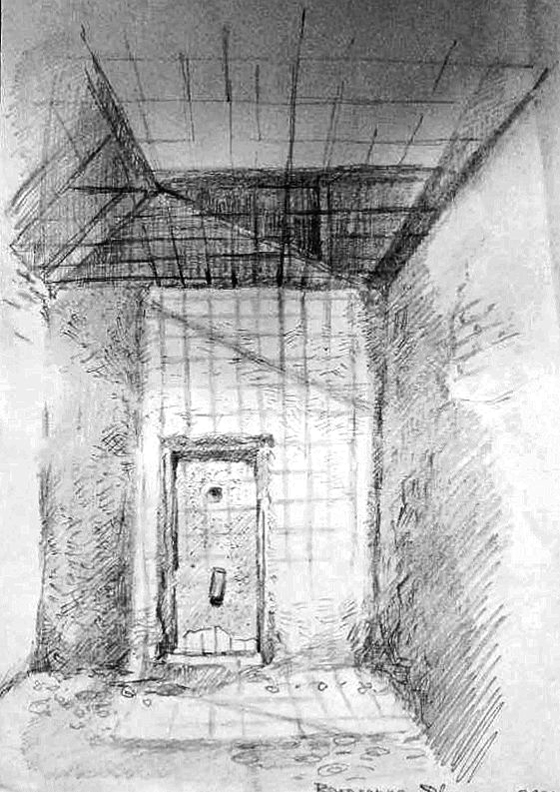

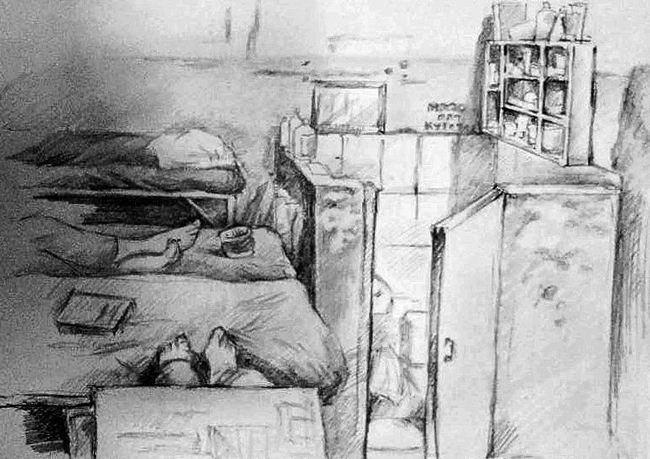

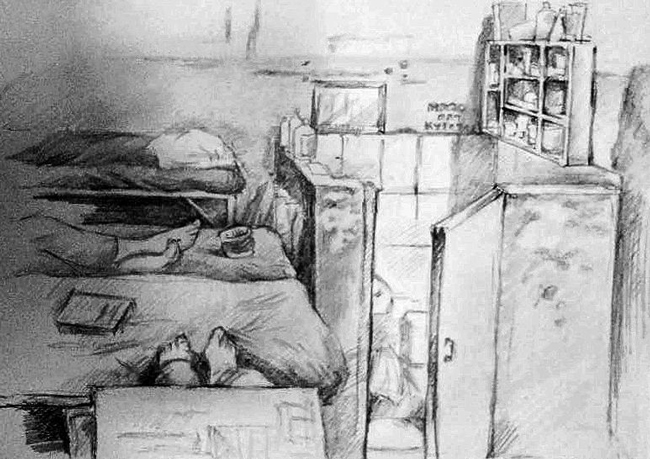

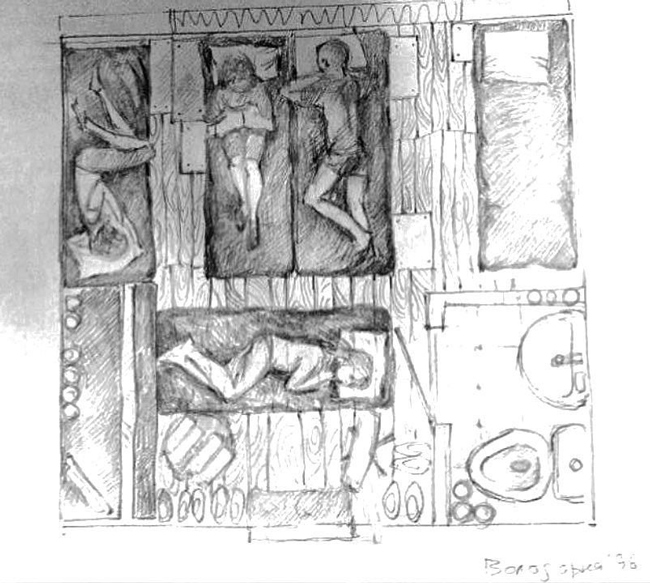

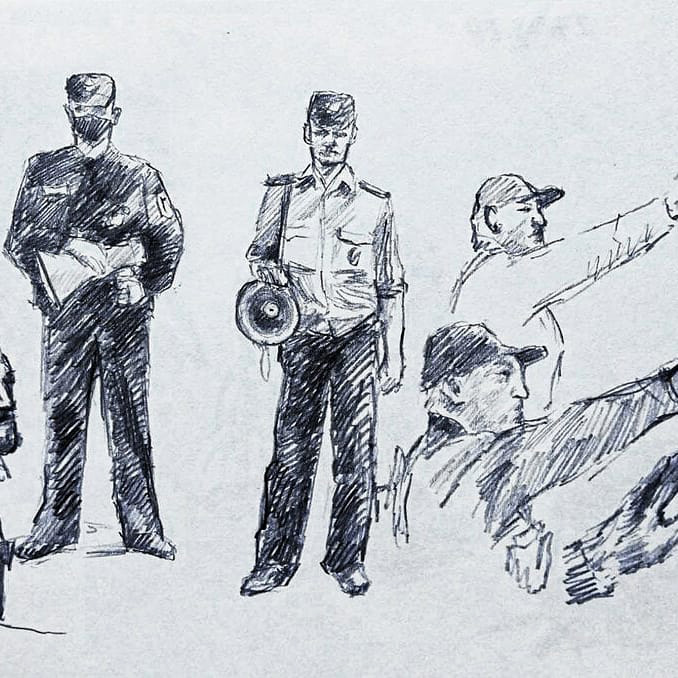

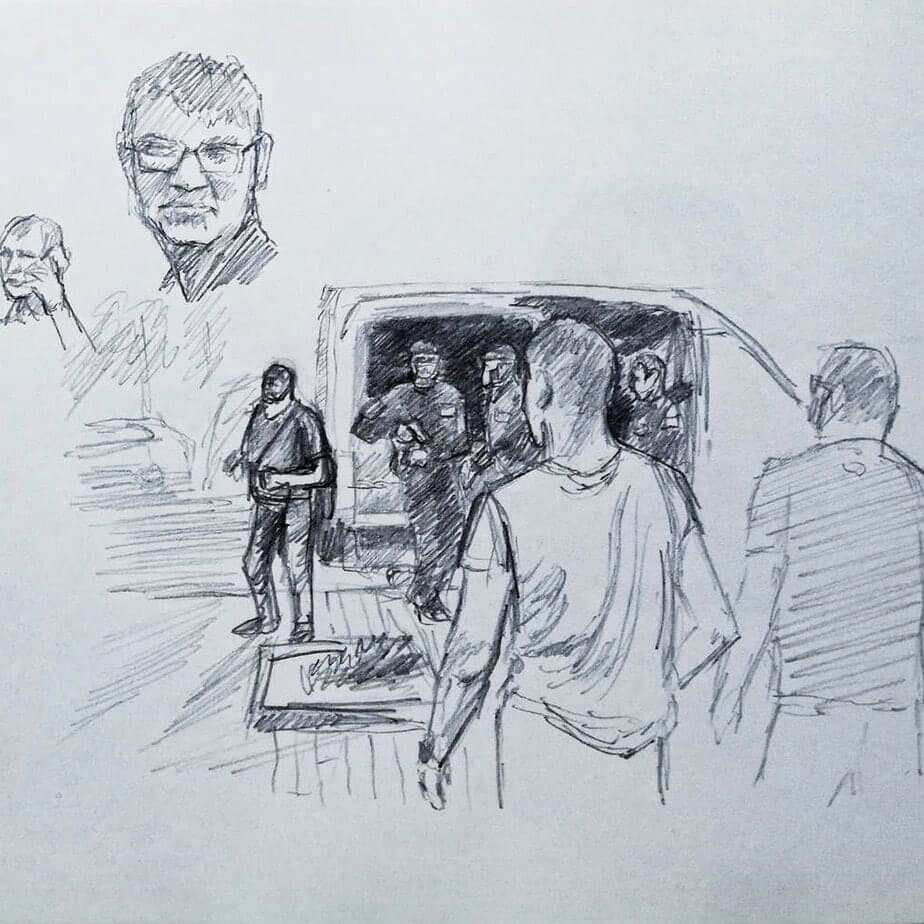

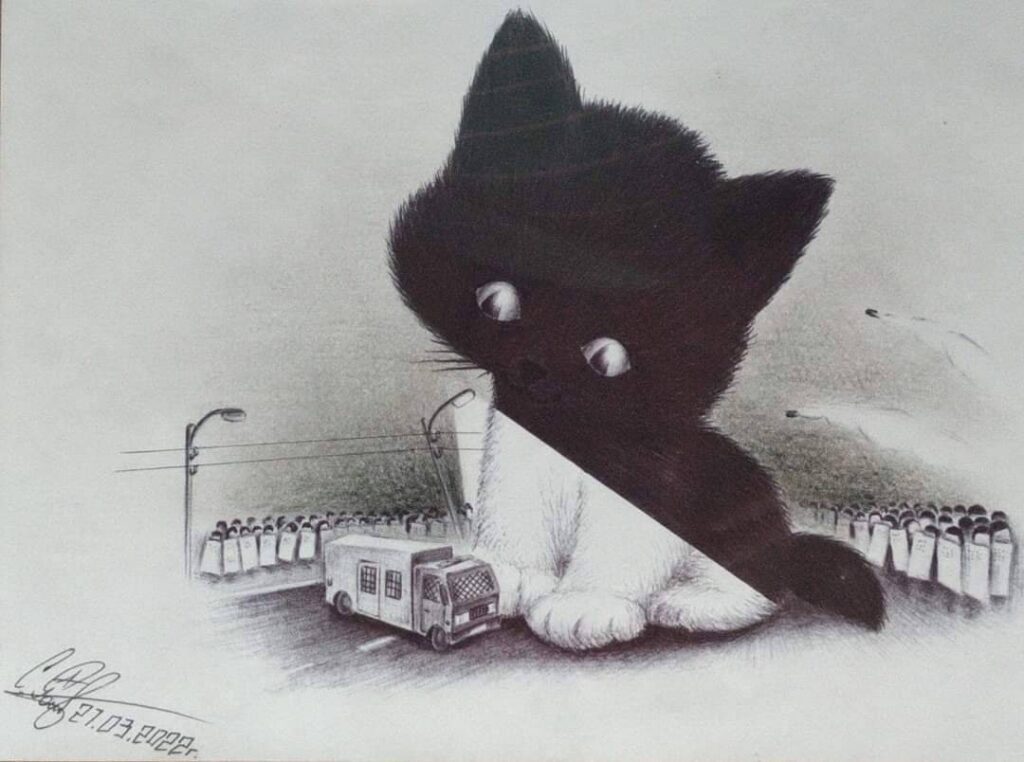

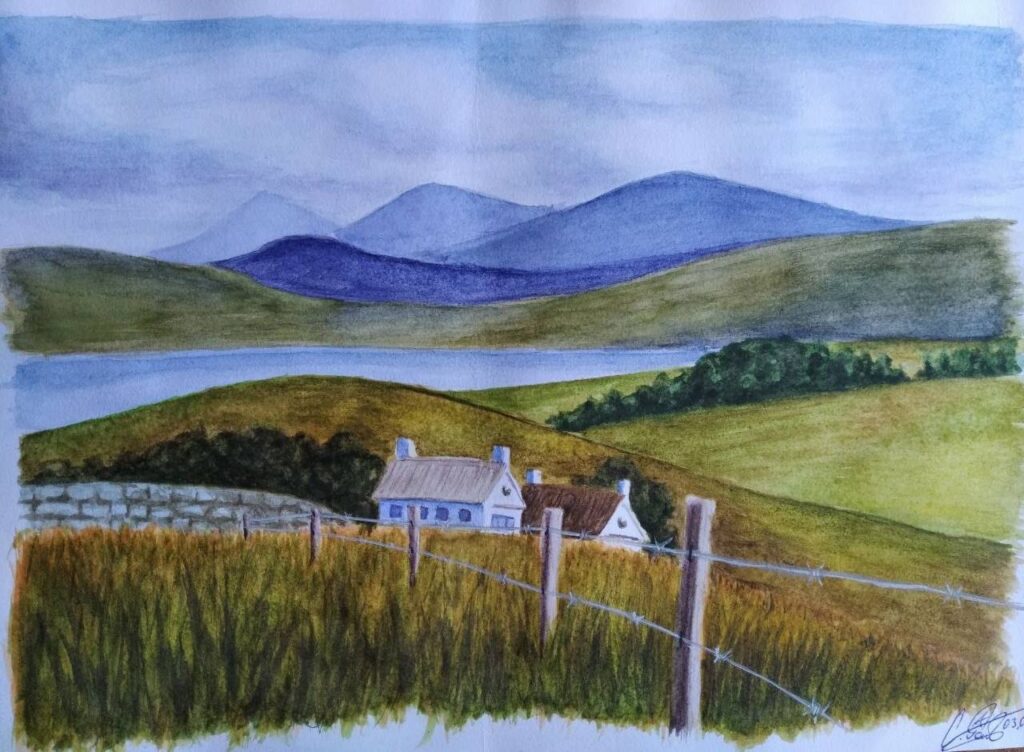

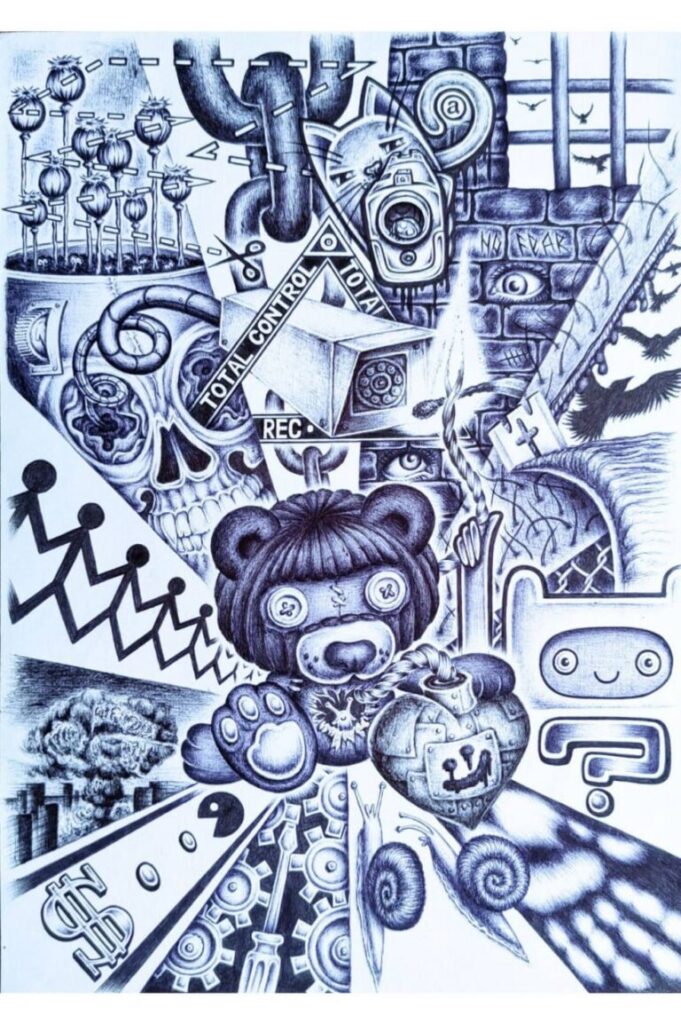

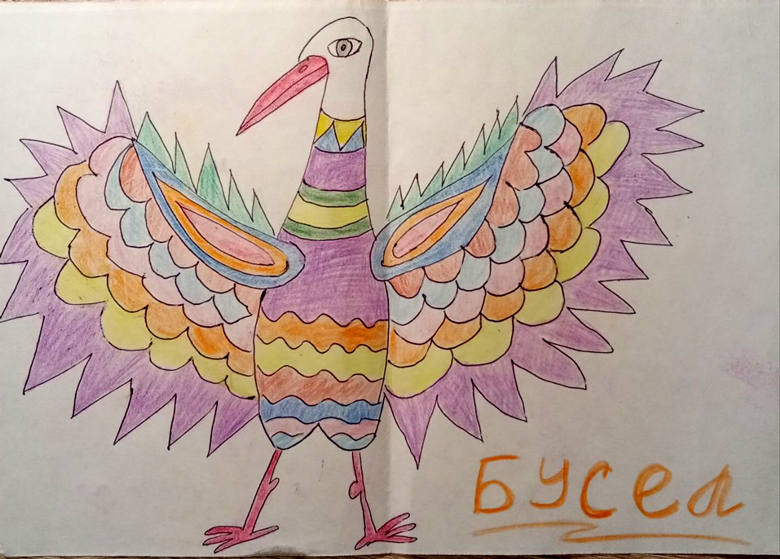

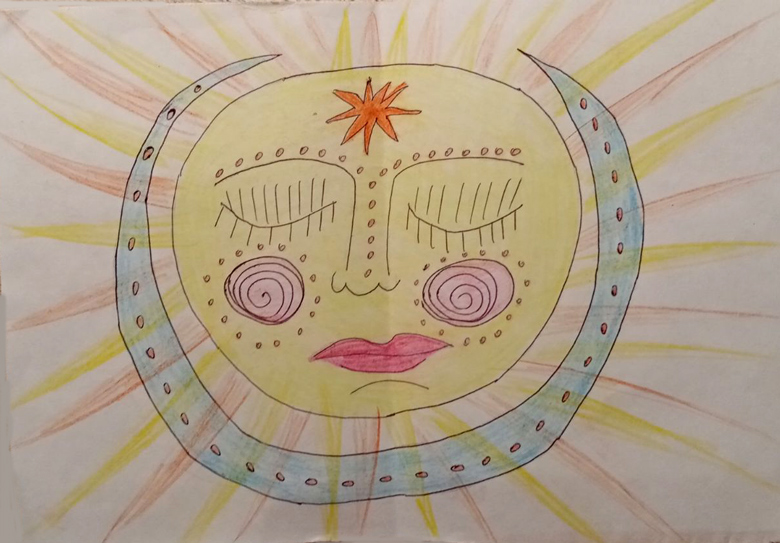

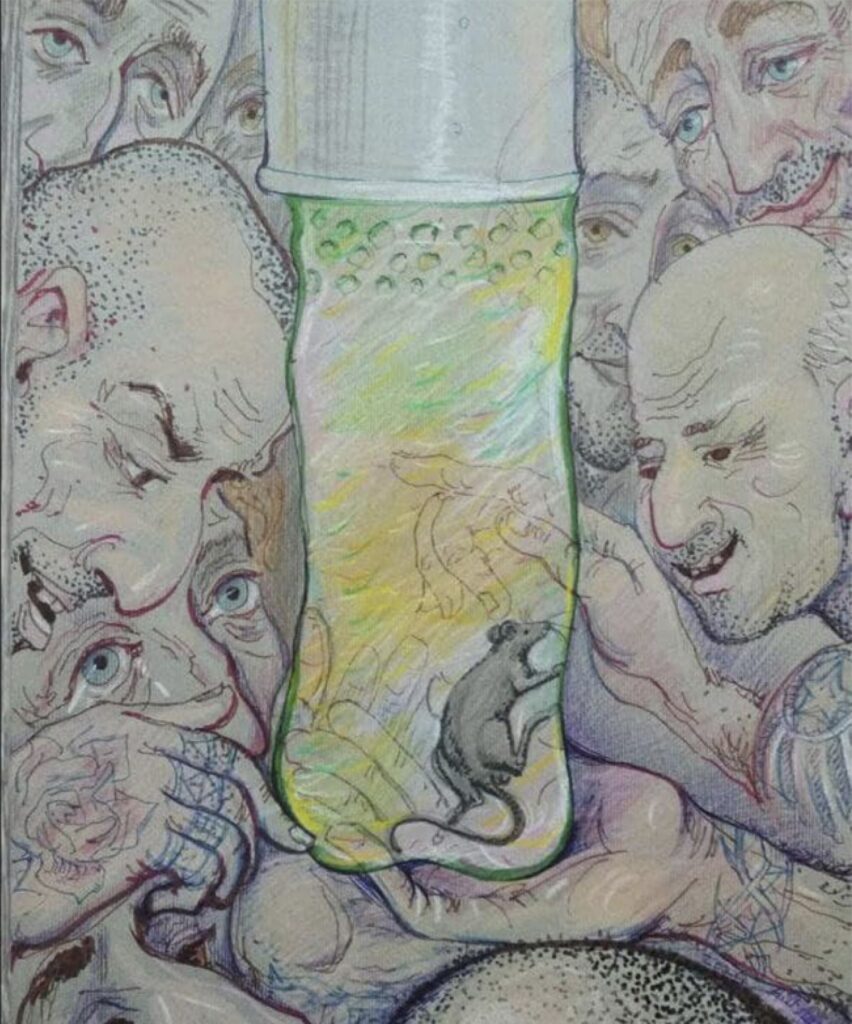

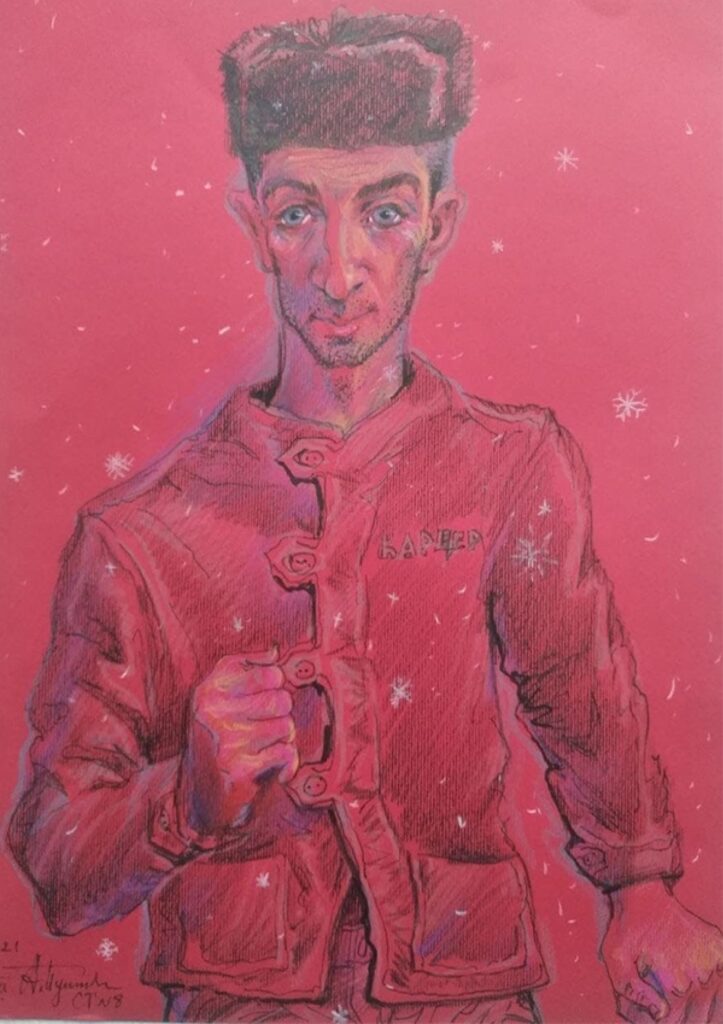

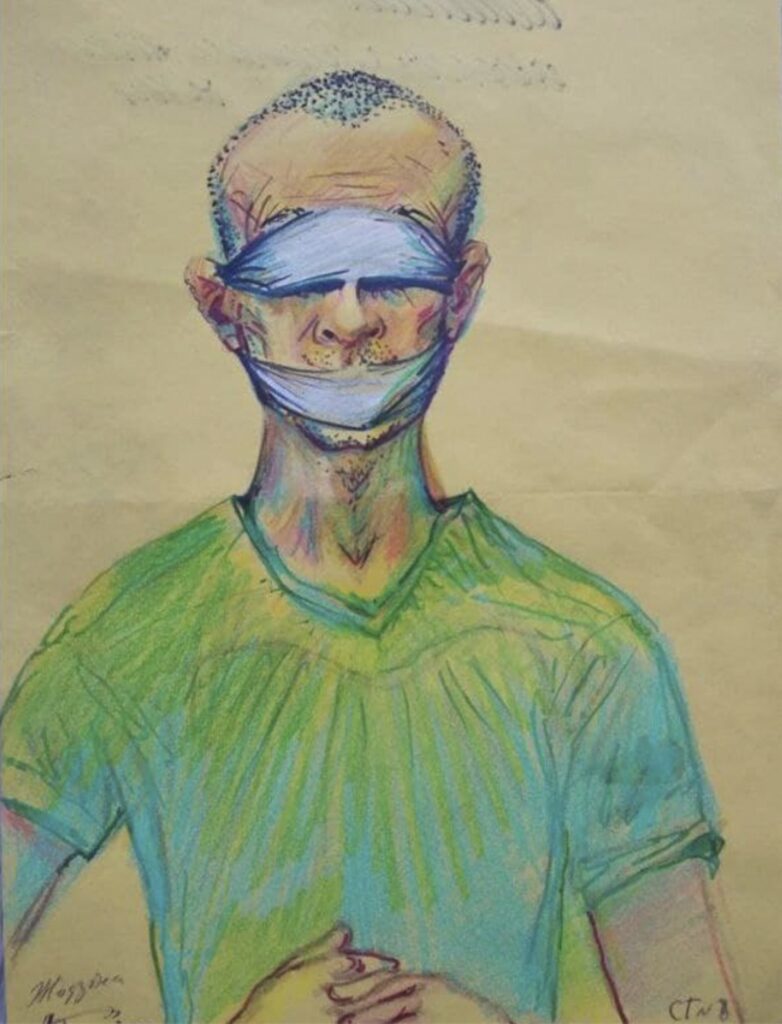

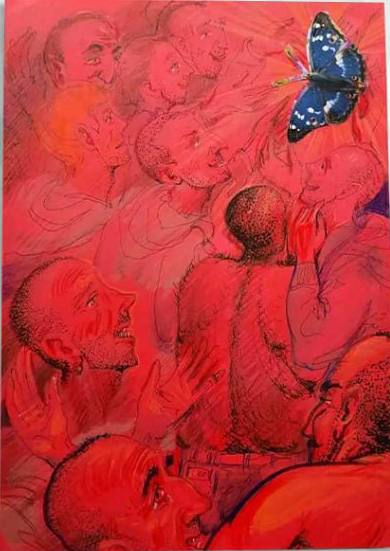

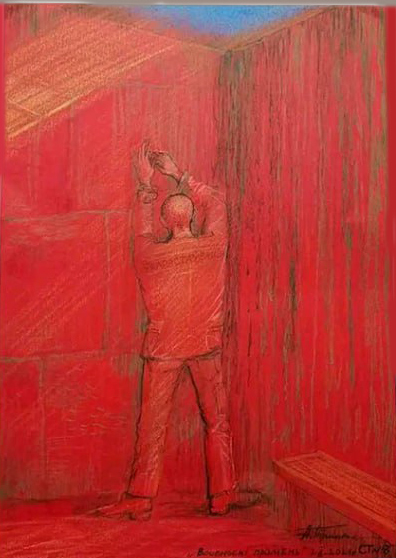

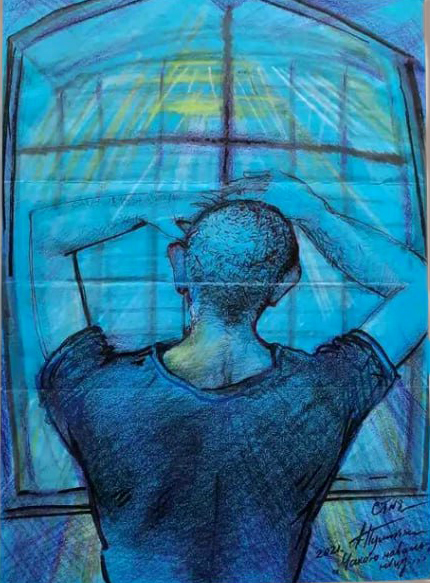

Also in the text, you will see drawings by Belarusian political prisoners and can read stories about how those who were behind bars in Belarus spent their New Year’s Eve.

The article was written in the first days of December. Until the next release, the exile of Belarusians from the country continues.

— The 2025 pardons became a surreal episode in the history of repression. How did you experience this moment yourself — more as hope or as another political farce by the authorities?

— Based on our human rights work experience, we are perhaps more aware than others of what is happening in the country from a human rights perspective. Understanding the realities of modern Belarus and seeing only intensifying systemic repression, I did not expect anything encouraging from the Lukashenko regime. And so it happened: the dictatorship once again used people to try to escape international isolation, while simultaneously getting rid of political opponents and dissidents within the country. These types of “releases” have become a monstrous new practice of forced displacement of people from the country.

— Many released individuals speak of different emotional states — from euphoria to emptiness. What did you notice in their first words and reactions that didn’t make it into the official media stories?

— In the fall, at the 2nd Congress for Political Prisoners, we presented the first results of our study on the Long-term Consequences of Imprisonment and Emigration—and this data shows all the medium- and long-term consequences awaiting those who have passed through the regime’s dungeons. More than 70% face depression, which manifests particularly severely in women. The average standard of living for former political prisoners becomes much lower than the world average (at the level of 50-60%, while the world average is 75%). And this is exactly what usually doesn’t make it into the media—the long path of recovery and resocialization, which can take many years. Public attention usually concentrates on emotional events or critical cases, but we want the individual not to be alone only during peak events, but to feel support and attention whenever they are needed.

— If we look at the pardons not as a humanitarian gesture but as a tool of power, what hidden goals do you think it solved?

— As I said above, one of the goals Lukashenko solved for himself was to escape international isolation and gain political points.

— Were there people among the released where you thought: “These ones definitely won’t be let out first”? What surprised you in this arrangement?

— It is surprising how Lukashenko decided to use personalities such as Mikalai Statkevich for his interests. Но, as we saw, that is exactly what failed. To this day, it is still unknown where the political prisoner Statkevich is located, as he refused to leave Belarus. When a person is released after years of pressure and censorship, the world outside can seem even more absurd.

— What is the most difficult ordeal today for a former political prisoner — not in theory, but based on your professional observation?

— I think the hardest thing is to synchronize with the world the person has entered, because prison and the rest of the world are two parallel realities. In one, the person is frozen — they are being tortured, trying to survive, while the other continues to develop and live by its own laws. In addition, the experience of imprisonment leaves indelible marks on physical and mental health.

“In the pre-trial detention center (SIZO), New Year’s Eve was almost no different from an ordinary day. The ‘lights out’ was strictly at 22:00, and around midnight, the corridor guards checked individually to ensure no one was getting out of bed — a report could be filed for any violation. Nevertheless, we still quietly woke up and congratulated each other at 12 midnight.

Before lights out, around dinner time, we tried to gather together and somehow celebrate the holiday: we set up an improvised table. This was important — just to be together and pretend that the day was still special.

In the colony, the regime during holidays was slightly softer. On New Year’s Eve, we were allowed to stay up until 01:30. We gathered in the educational work room, set tables there, could sit together, watch TV, go out for a smoke. This was already very different from the usual schedule.

We congratulated each other, of course, but in different ways. In the colony — exclusively verbally: warm words, wishes. Giving gifts was forbidden. In the SIZO, however, the girls and I sometimes exchanged small, memorable trinkets.

In the SIZO, everything was as simple and accessible as possible. We made an improvised cake from layers that could be bought in the prison shop, condensed milk, and prepared sandwiches. Everything was assembled from packages and purchases. If someone had nothing — it didn’t matter, everyone was treated. Everything was shared.

In the colony, tables were also set collectively, but for political prisoners, the topic of sharing was complicated. On regular days, this was considered a gross violation and punished with a report, so we were cautious even on New Year’s. Mostly, everyone still ate their own food.

In the colony, you could watch TV. Standard New Year’s programs like ‘Goluboy Ogonyok’ were on. This created at least some sense of celebration. In the SIZO, we didn’t have a TV — in Gomel, it’s not allowed in cells with political prisoners.

I can’t say it was a truly joyful or special day. Но even a small change in the regime, the chance to sit together a bit longer than usual, talk, watch TV — all of this was perceived as something important. In such conditions, any deviation from the routine becomes significant”, — says Kristina about New Year’s Eve in a Belarusian SIZO and colony, who served time under Article 342 of the Criminal Code of the R.B..

— Are there stories of released individuals that you still cannot share publicly — but which best characterize the atmosphere of these pardons?

— It would probably not be very ethical to share specific nuances, but many who have come out have repeatedly shared and continue to share their stories themselves, as well as the frustration they faced after surviving such treatment.

— The authorities often use the pardoned as an element of propaganda — as if to say, “everything is fine, we are letting them go.” How much freedom is there actually in these “releases”?

— If we are talking about people who remain in Belarus after the “pardon” process, they face a series of restrictions and continued pressure on them and their families. For example, many are forbidden or “strongly discouraged” from leaving Belarus, forced to appear in propaganda segments about how prison corrected them and what a bad choice they made in the past, and pressured to write to human rights activists and helping initiatives to find those who haven’t been arrested yet in the fight against “extremism” and “dissent.” Besides this, the person is left with classic post-prison problems: physical and mental health, desocialization, an atmosphere of fear, inability to find a job, and so on.

If we are talking about those who were forcibly moved to Lithuania, these are the same recovery problems plus the fact that one day a person is in custody planning their life a certain way, and the next day they are taken to the border of another country with a bag over their head, without documents and in a prison uniform — this undoubtedly knocks the ground from under their feet.

— How much has the map of political prisoners changed after the 2025 pardons? Do you feel that the system has become more cynical… or conversely — that it has shown weakness?

— In 2025, we encountered a practice never before seen in the modern history of Belarus. Perhaps something similar was present in the 20th century during the heaviest political crises in our country, namely the forced expulsion of dissidents, which can be called mass expulsion. The international human rights community watches with great trepidation as an aging dictator commits increasingly severe crimes, including crimes against humanity, for the sake of maintaining power.

— People on the outside often expect “loud words” from the pardoned. But what do they usually want to say themselves — before they start looking over their shoulder for their safety?

— Connection with loved ones and their inner circle — that is the first thing a person strives for to feel a safe space and find their footing.

“I didn’t make it to the colony and spent the entire detention period in the SIZO. I celebrated New Year’s almost like a school play: we made a festive cake from cookies and condensed milk, prepared all sorts of treats. We watched TV — concerts were playing all day. At 22:00, lights out and power off.

At midnight someone would shout through the window, but most were already asleep by then. Something like that.

We cooked whatever we could from what we had, but the most common thing I heard of was a cake similar to the Polish ‘kopiec kreta’ (mole hill): You grind cookies by hand, boil condensed milk (just throw a few packs into a basin with immersion heaters), melt butter. All of this is mixed, plus candy, plus fruit if available. True, the cleanup takes longer than the cooking.

They only take the handles off the basin in which you boil the condensed milk so that ‘evil convicts’ don’t tear them off and sharpen them into weapons.

If someone in the cell draws well, they get orders to draw postcards that will later go to relatives by mail. They try to do this in advance because ‘slow mail’ takes up to a week,” — Dmitry tells about New Year’s Eve in a Belarusian SIZO, who served time under Article 342 of the Criminal Code of the R.B..

— Honestly: are the 2025 pardons a crack in the wall or just cosmetics on the facade?

— From our point of view, the recent practices regarding how people left places of detention speak of an ever-deepening systemic crisis in the sphere of freedoms and human rights.

We see how the state, led by a dictator, continues to consistently destroy the institutions of freedom and human rights.

And now, repression and subsequent criminal prison sentences are no longer a sufficient measure for a regime that was existentially terrified in 2020.

В modern Belarus, repressive practices continue both in prison and after a person has left, and also take the form of the now-unconcealed pushing of undesirable individuals out of the country of their birth.

How much further will this dictatorship, bristling with police batons, go?

— On New Year’s Eve, many expect a miracle. What “miracle” is actually possible today for a political prisoner in Belarus — and who is capable of making it happen?

— Every person, regardless of the country they are in, can show solidarity and safely support political prisoners. For this, all possible tools exist within initiatives and organizations.

— When will the next political “New Year” take place — into what reality will Belarusians wake up in 2026?

— Predicting such things is a task for political analysts. We continue our systemic and practical work to support political prisoners, former political prisoners, and their families, and we call on everyone around us to do the same using all available tools.

Nottoday reminds us that many Belarusians remain behind bars for the brave choice they made in 2020, before, and after. We urge you not to forget those who will not be able to spend this New Year with their loved ones. Your support — from an ordinary postcard to helping organizations and initiatives that support Belarusian political prisoners, both those still behind bars and those already released — is extremely important. Solidarity is our weapon!