Ivan Treptow worked in liberal NGOs in Russia for a long time, but life, as he says, threw him out of this “golden cage.” Grants and “perks” were replaced by unemployment benefits in Berlin. However, along with this came the time to pursue dreams and goals Ivan had set since childhood — to write and engage in literary creativity.

During his new life as an emigrant, Ivan has managed to create several works: from novels and poems to collections of short stories. Nottoday managed to attend one of the “covens” where Ivan read a poem about Berlin, after which we decided to introduce you to his work.

By the way, one of his novels will see the light of day this spring and will be available in a printed edition.

In this interview, nottoday will try to introduce you to the main themes of Ivan Treptow’s works, a bit of his poetry, and his path to literature. There will also be talk about how the abyss has already opened its maw, and we are either a step away from falling or already in it.

How you became a writer

— How did you come to literature? Where did it all begin? And why did you immediately dive into this “dirt” — dystopias and social dramas about lawlessness? Do you really not have enough stress in your life?

— It all started in school, probably. When I was a teenager, I was already writing profane poems, and that was really my first experience in literature. I literally trashed everyone: teachers, classmates, and just random people, sometimes using straight-up obscenities.

And then my parents busted the whole thing. I went away to a summer camp, and they found my diary with the dirty poems. And that was it, I was shut down. Maybe that’s where it all started… I don’t know.

To be honest, I really like the “bottom” of life. Ever since I was a kid, a teenager, as long as I can remember, it always interested me. How it works — that’s a mystery to me.

When I was thirteen or fourteen, besides profane poetry, I was into rap; I found the rhythm and rhymes interesting, it felt like I was listening to relevant poetry. As a teenager, I wasn’t very social, I sat at home reading books, and some of them really hooked me. Apparently, it all just came together.

Why dystopias or social dramas? Honestly, the constant talk about “trauma” in literature really annoys me; it’s a psychological newspeak trying to crawl into every crack right now. But if we talk about the choice of themes, I think the reason lies in the provincial Russian town where I spent my childhood and youth. I hung out with “gopniks” (street thugs) and outcasts all the time. Actually, I hung out with different people, but I wasn’t attracted to kids from “decent” families. I had these “gopen” buddies. The guy who taught me how to ride a motorcycle—he actually OD’d on pills and crashed to his death.

And another one of my best friends, when I was in third grade… I wrote a story about him. He was kicked out of school, then he did time—I don’t know what for—and he’s no longer alive. Later, when I went to university and moved to Moscow, everyone was more “proper,” but I had seen enough in my childhood, I guess, and that left an imprint on me.

I’ve always loved dystopias, but only now am I approaching them seriously in my writing. I have a plan to write a dystopian novel. I feel like I’m already pregnant with a novel.

Berlin: Escaped or Stuck?

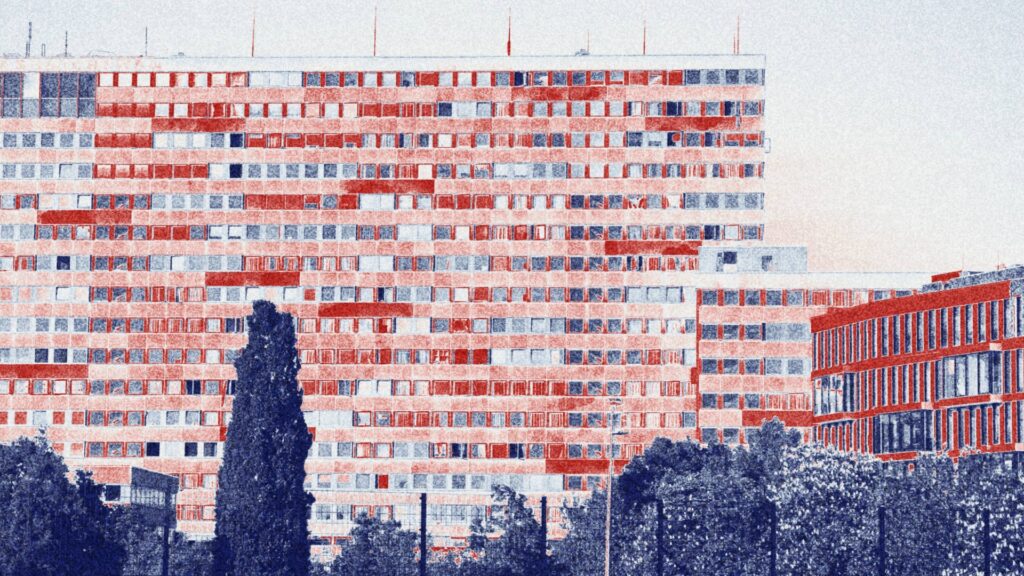

— You’re in Berlin. You write about the rotting 90s and the coming collapse. Are you hiding from the chaos here to analyze it from a distance, or is this your personal “New Land” where you’re trying to build a life, but the past still won’t let go?

— Honestly, I ended up here quite by accident. I didn’t plan on coming specifically here, let alone to Germany. It didn’t attract me at all. Though, when I was twenty, I was heavily influenced by German leftists who came to Russia to volunteer in human rights NGOs. At one point, my best friend was German. I observed Germans closely then, but the desire to move to Germany didn’t appear. My flight here just happened. For obvious reasons, lol. And now I’m trying to squeeze some pleasure, some fun out of it. But I don’t consider myself a sufferer — it just turned out this way.

When I was still “on the ground,” in a familiar environment where everyone spoke Russian—I’m talking about Russia—I was really scared to write what I thought. Not just because of the prospect of a criminal case, which was easy to get in Russia in recent years. From age twenty to thirty-two, I lived with the thought that the cops could come at any moment. I’d jump at a knock on the door, especially early in the morning. And parallel to that—a feeling that for everything I wrote, I’d be literally lynched.

Basically, I was genuinely afraid to write the way I wanted to. In my twenties, I wanted to write radically. I wanted to tear everyone a new one, to trash them. I truly believe there is a lot of rot and filth around. And all this hell happening now is not accidental. I’ve spent enough time in the activist and liberal circles, I’ve seen enough, I’ve had my fill. And honestly, I think many of these people fully deserve everything that is happening.

And this feeling—living among people who don’t know my language and will never read this, unless in a translation much later—it somehow gives me relief. A certain distance. You ask about the rotting 90s and the future collapse. Yes, it’s actually seen better from Berlin. This distance turned out to be important—I didn’t expect it, but it happened. Because when you’re inside, it feels like you can write right from the moment. But I think an artist needs detachment, a look through a frosted glass at reality. And Berlin gave me that. As for whether I’m hiding from chaos—I don’t know.

***

The shawarma-man is tired,

Your shift has passed,

You’ve rolled the shawarmas –

The joy of a greedy mouth,

On a massive poultry farm

A chicken lived freely

And likely didn’t know,

What fate awaited her,

That the executioner-laborer

Sharpened a keen blade,

Shawarma-man, our lad,

Bought your body whole.

How they laid you out

For the fools to see

It wasn’t enough they killed you,

They put you in the shop.

And on Karl-Marx-Strasse

Wingless you lie,

With a greasy, hairy hand,

They carried your life away.

On a Sunday, hungover

The shop is shuttered tight,

Left without food,

With a spinning head

Searching for nourishment,

I am emboldened by you.

Half-naked, I acquired you

For a colored paper, crumpled,

Pulled from a pocket.

You are wrapped in a shroud

Of white pita bread,

With greasy sauce on top

The soul will erupt.

I gnaw at your body

It is foul, oily,

Yeah, the food here isn’t great,

Let’s be honest — it’s crap,

And I started to feel lousy

And quite unwell.

An innocent bird’s soul I destroyed

With a can of soda, I sprinkled her corpse.

The shawarma-man cackles,

Staring into his phone,

Oh, what a foul giggle!

And the mustache twitches,

And the knees tremble

Of the chicken-killer.

Not finishing my meal, I run,

Rushing toward the U-7.

But the train was full of people,

And that filthy giggle followed me.

2025, Berlin

Who “spoiled” you?

— Obviously, you have a foundation. Where did you get this intellectual base — are you a techie, a humanities person, self-taught? And which authors pushed you to write about harsh and unaccepted things without looking back at conventions?

— It sounds cliché, but lately I’ve really been into Limonov. This summer I reread some of his works that I’d missed before. And the old immigrant Limonov — before the collapse of the Union, before returning to Russia — that’s true power. He’s a really talented guy. Everyone knows “It’s Me, Eddie,” but he has a bunch of powerful novels that provide a unique perspective on emigration. And in general, he inspired me — in a good way — to stop giving a damn about everything. Limonov is something else.

It’s interesting that I can sometimes see with my own eyes who he “stole” from. From Céline, for example. And Céline was a revelation for me. I really dig his style — though I only read it in Russian translation, I don’t know French. Those “Célinesque” words, phrases, that optic… anarchist-nihilist, I guess. It felt very close to me.

Then I liked Jean Genet. True, it’s hard to read him for long, but some things really hit. Also anarcho-nihilism — my thing. I read various things, actually. For example, Kerouac’s “On the Road.” As a travelogue, it was a great anchor for me when I was writing my last novel.

Who else… Who knows, man. I like some magical realism too. Generally, Latin American magical realism — Cortázar, Borges, Márquez — it all resonates.

Latin American acquaintances told me — look, man, we live in total crap. To put it simply. It used to be military dictatorships, now it’s ostensibly democracy, but in reality — it’s also nonsense. Hellish poverty. Though the countries are beautiful, nature is great, people are cool, but reality is what it is. Even in Argentina, which now has a lot of emigrants from the post-Soviet space, especially Russia — in Buenos Aires, many are simply starving. They go for violent robberies because they have no choice.

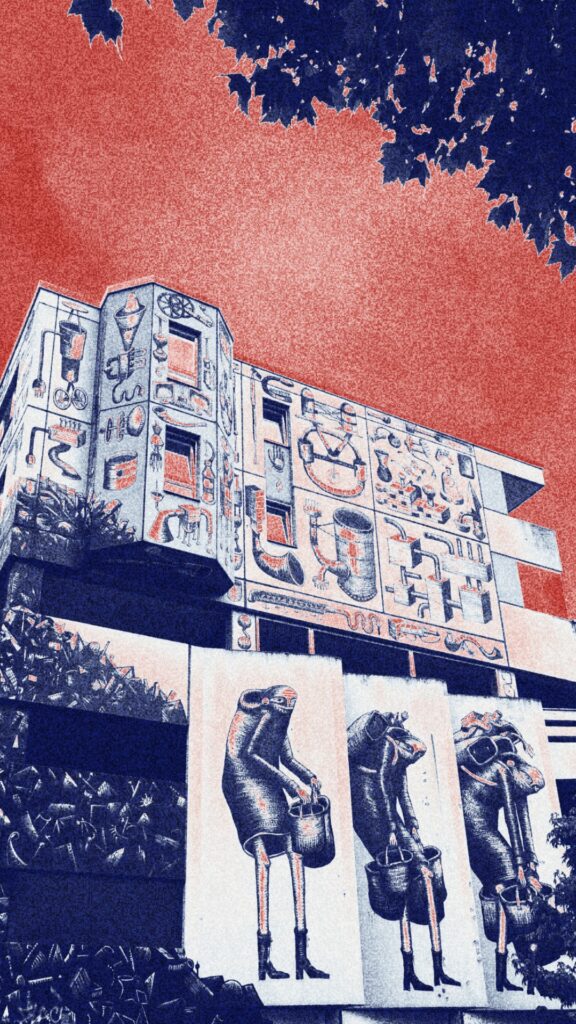

And they say: that’s why we turn to magical realism. We imagine a better world, a better reality, because everything around us is structured in such a way that it’s otherwise impossible. And that’s very close to me, actually. Because the provincial Russia I saw was based on the same logic.

I remember my grandma’s village in the 90s. I saw them plow the garden with a tractor for a bottle. And how everything could be done for a bottle — it was the best currency. How the road was so shitty that you needed two tractors to pull out one car. Men died from moonshine, everyone was fighting with each other. And this magical realism is a way out of the grayness, the disorder, the ruin. It’s like inventing a better reality for yourself because the one in front of your eyes — well, it’s like that.

Where Ideas Come From

— How does it work for you? Does a plot detail appear first — like how a bear might maul the hero at the border (a fact) — or does it all start with a metaphor, an image, an internal flash? What triggers the creative mechanism: cold logic or a psychedelic impulse?

— Sometimes it just happens: an image appears, or even a single word, or a phrase — and you catch onto it like a spindle. And everything really starts from there. It can be a plot detail or a pure image. I don’t know. Sometimes a word keeps spinning in my head, or I’m walking down the street and something flashes. I used to lose it often, but now I try to write it down when something like that comes. And from that, you start composing.

When there is a plot — that also helps a lot. Though in the end, you almost always deviate from it significantly. Но it’s like a map in your head: it’s there, and it provides support. For example, my last “artifictional” novel — “Destroy Us” — was inspired by Céline’s “Journey to the End of the Night.” Where the hero ends up in Africa: black Africa, no comfort, harsh tropics, pitch-black darkness. That’s where his hero finds himself. And I found that an interesting route. I’m not repeating it, but “Journey to the End of the Night” became a real inspiration for my own journey in the novel.

And, to be honest, I think that in writing, everyone steals and peeks from each other — and that’s normal. In language, in style, in plot. The question is to see enough different things, to gather a lot of stuff — and then invent something of your own on that soil. That’s the trick.

Many things in the stories and novels are my observations from life, which, of course, are cranked up, because life itself isn’t intense enough to build a plot straight from it.

The Essence of Dystopia: Collapse and Control

— When you take on a dystopia, what truly scares you? Total state control or how people voluntarily give up their freedom?

— On one hand, the trend is that the state in many countries decides less and less. In many places, corporations and international entities rule the roost. And the state there is just a screen. But my life experience turned out to be in that part of the world where the state still tries to crawl into every hole. And this is interesting: in Germany, the state is much more all-encompassing. Under the guise of care, it really keeps an eye on you. In Russia, I lived half my life not at my registered address — and it didn’t bother me at all. But living without registration in Germany suddenly turned out to be a big problem. There you go.

People voluntarily giving up freedom… Man, I don’t know. I really got stuck on this question. What’s scarier — total state control or voluntary surrender of freedom? Who the hell knows. Voluntary surrender… life is structured now so that you are either inside the system, using services, and they collect tons of info on you. Or you drop out of normal life, which is very hard: not using Google Maps, not using Zoom — it’s almost impossible now.

Overall, the question isn’t simple: people aren’t handed a ballot “for freedom” or “against freedom.” In words, we are all mighty lions, all “for freedom.” I think even the slickest scumbags would say that. But besides freedom, there are tools of mobilization and control. They explain it to you clearly: if you don’t integrate into the system, you’re screwed.

Life in Germany is an example: as a foreigner, you have to earn “good migrant” points, social credits — learn the language, work, don’t sit on benefits indefinitely, live very law-abidingly. Then you get bonuses. The ultimate bonus is the passport. That’s what it all leads to.

— One of your novels is built around technology. What is your attitude toward technology? Do you think technology today is no longer a tool of freedom, but almost a ready-made infrastructure for the next dictatorship? Where is that red line that we’ve already crossed?

— The idea of the novel I’m pushing now: the private sphere has completely fallen under control. It suddenly became very visible. A person can be pinched on completely unexpected sides. Those who own Big Data really have huge power: they can try to predict behavior, electoral behavior, anything. And that, of course, is very dangerous.

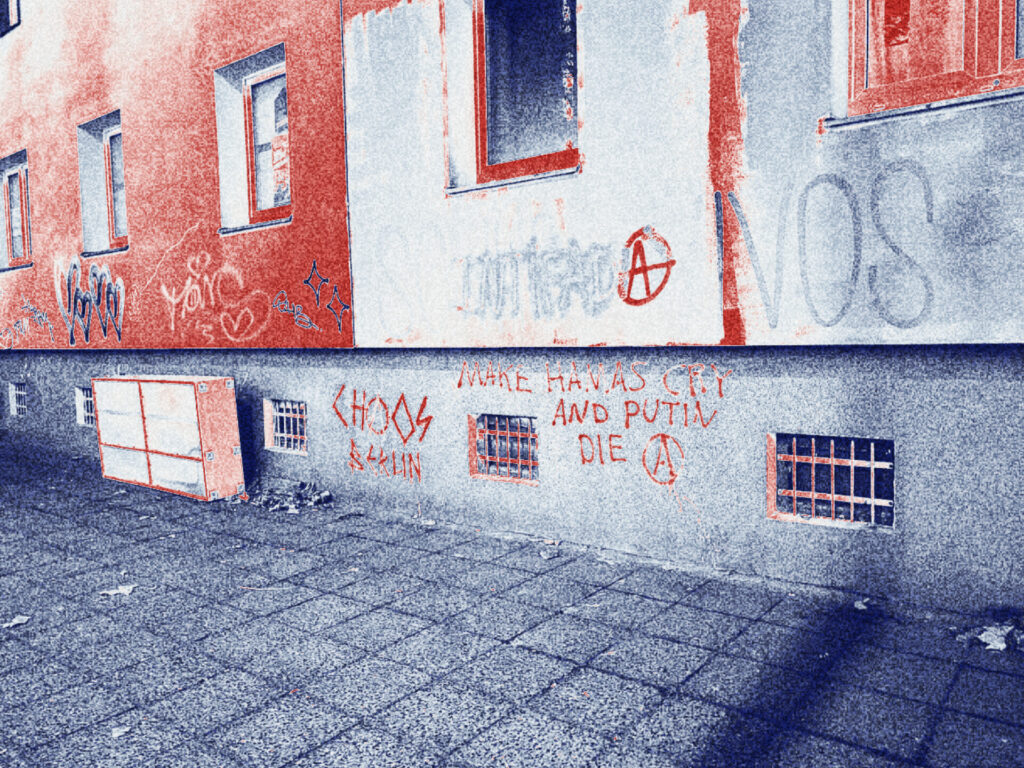

It’s no secret that technologies help track, and this is especially clear now. Just yesterday in Berlin, they passed a hellish police law that gives cops a million rights to surveil. Including facial recognition technologies.

Technology itself is blind. A train moves — and that’s neither good nor bad. A smartphone exists — and that’s neither good nor bad. It matters who uses it and why. And in that sense, my conclusion is extremely grim: everything is pretty bad.

There is Varoufakis, the former finance minister of Greece. He wrote a book about digital feudalism: corporations own everything, they’ve entangled the world, and they take a growing tribute from us. Even if you don’t play their game directly, you still feel it on your skin.

For example, Airbnb makes housing more expensive everywhere. You might never use Airbnb, but the rent goes up, and you suffer. Tinder created a strange market for love — and it affects even those who aren’t on Tinder.

And the scariest part — these technologies are in the hands of Trump’s devoted buddies, ultra-right corporate bosses. We are now quite close to what Jack London described in “The Iron Heel”: corporate fascism. It’s unpleasant to realize, but yes, those are the trends.

People are shitting themselves: that there will be no work, everyone will be thrown onto the street. Science fiction writers dreamed that with robots and AI, ordinary people would have free time for art, love, and rest. But today they tell us: you will live under a bridge and eat out of a trash can.

Every turn of technology is simultaneously a chance for liberation and a chance for enslavement. The Internet once seemed like a way to escape TV and state propaganda. But it became a means for even greater control, squeezing out juices, and reducing autonomy.

Will we manage to tame the internet? I don’t know. Old states like Russia, Belarus, Germany can still mess with everyone. But a large part of the world lives in countries where the state is nominal, and real power is taken by technological feudals.

And, it seems, we will live in a world that they are rebuilding for themselves.

— Is dystopia for you a warning or already a description of the inevitable end?

— No, I don’t think there is any end — that’s even scarier if you think about it. There is constant struggle, constant fuss. But it’s both a warning and a description — I don’t know, I think we are both at the same time. That is, there is no end, but the description of darkness is necessary. And the warning too.

In this regard, literature, I think, is much more interesting than all these social sciences — political science, sociology, and so on. They have shown their toothlessness. They can’t tell us anything radically new about the world we live in. But literature can — through imagination, through building onto reality. It can both terrify us and inspire us, and, I don’t know, through some magical realism, switch on our imagination and help us find a way out. And I think there is no “end.”

Social Drama: Man at the Breaking Point

— What do you think is the main “social trauma” today? Loss of money? Loss of faith in the state? Or something deeper — the loss of the ability for normal human relationships?

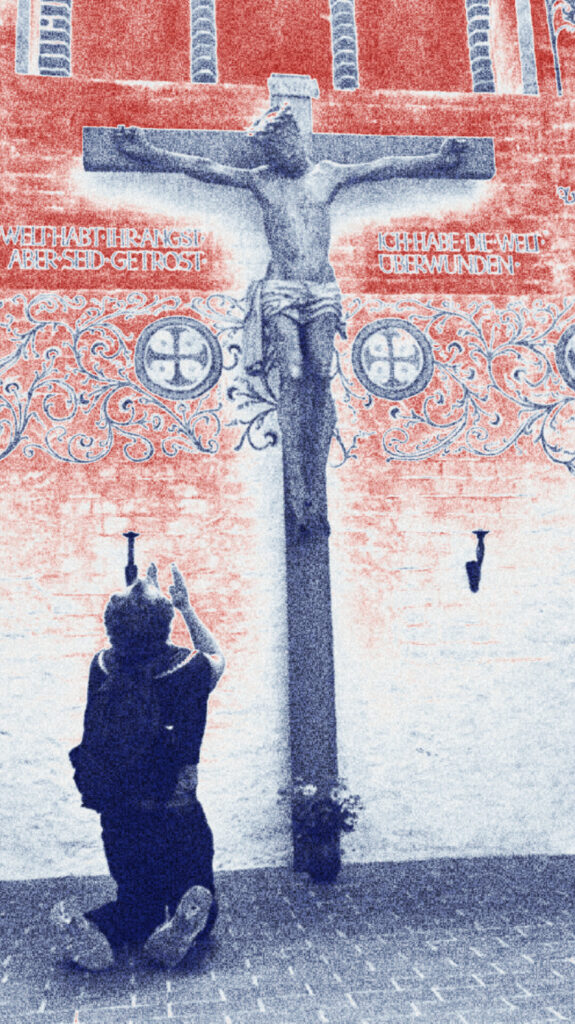

— I would say—it’s the loss of faith. I think anyone who still believes in the state is, well, probably a total sucker. But generally, a person needs to believe in something—not necessarily in the Lord God, but in some kind of idea. And it’s probably a very interesting moment when a person suddenly loses that faith for some reason. It could be faith in the social system, or something else.

In general, I find it very interesting to observe disillusioned liberals or disillusioned fascists who thought they’d build a white paradise for the white race, but something didn’t work out. All of this—long story short—is an interesting moment: a person believed and believed, walked and walked, and then suddenly, so to speak, they crapped themselves. And they’re standing there, looking around: how do I even live now? That, I think, is curious. And they’re like: what do I do now? Just live like a normal person? That’s also a bit of a joke. So, what’s there to do, then?

Yeah, I think everything else is just a derivative: the loss of money… Although no, actually—it’s all about the loss of money. All of this is generally about money. But perhaps other writers will write about that important story better than I can.

— Your stories are full of violence and cynicism. Why, in your view, does a person at a social breaking point lose their humanity so quickly and turn into a surviving animal?

— I don’t know, actually. I’m not even sure that’s the message I want to convey—that a person loses their humanity that quickly. Another thing is that I’m interested: I don’t think it always happens rapidly; it’s different for everyone. But I’m curious about when a person’s glossy layer—which, I feel, tries to plaster over their beastly nature—gets stripped away. And when that plaster falls off and we see the gut—that, of course, is interesting. Though, again, that’s all just our imagination.

And to some extent, we are all surviving animals. We all want to eat, to copulate, to stay warm, to get our hands on something. It’s just that sometimes we hide behind some “high-minded matters” for the sake of all that.

— Do you believe that fatalism is an honest way to describe modern life? Or do your dramas still leave a minimal chance for the hero to find salvation or, at least, dignity?

— Yeah, look, I just like it… Fatalism is a convenient way to describe life. Fundamentally, I don’t know how honest it is, but it can be effective. And there’s something attractive about it. You can imagine there’s a fate a person tries to escape from, but it catches up to them anyway. That’s pretty cool to describe.

As for a chance at salvation, yeah, I think there is one—as long as the bear didn’t eat you. Salvation or dignity—that’s also a good fork in the road: you can, after all, die beautifully. With music! I just like describing the abyss. I think we are all currently either standing on the edge of the abyss or actively rolling into it. And the sooner we realize this, the easier it will be for us to orient ourselves and actually do something, instead of just moaning on social media.

What pisses me off about current life is that people stubbornly pretend like everything is fine. But actually, guys, nothing is fine—we’re all screwed. And I think literature can, like, explain that to us clearly.

***

At Bellevue station

I’m puking without cessation.

Beautiful views –

Four cakes!

One framed the ticket machine,

Two settled more vilely

By the drink vending points,

The fourth lies modestly under the bench

Freshest ones!

Red ones, with tomato paste

Mother Nature from my vent

Gave birth generously,

Dressing them up with stomach juice,

Vile grass!

Knocked me off my feet, a knockout!

An evening of solidarity with Russian dissidents,

Cut short prematurely.

It robbed me!

Get lost! S-Bahn, rare squinting passengers,

Ordnungsamt, Sicherheitsdienst,

They’ll pinch you yet,

Dogs,

Pat the pocket,

Seems like nothing’s lost,

Get the hell out!

Every station

Is taken heroically,

Don’t fall asleep, don’t let the nose dip,

Don’t fall onto the neighbor,

Don’t end up in Grunewald, in Potsdam,

Here it is – Charlottenstan

waiting for the night’s lodging,

Pissed-on station bushes, bare,

In places, someone even left a load,

Charlottenstan, Charlottenstan!

Berlin is your charlatan-city,

Deception-city!

It promised us love, careers,

Instead, you get the shaft!

Herr Treptow, let’s go,

Here is your appointment for sleep.

Night, Wilmersdorfer Strasse is pitch black,

Empty as a whistle,

Life itself caught a cold,

They traded-bought-drunk-ate-smoked it all away,

Life is bad! As always – they whined,

And now no one and nothing,

Only gopnik-teenagers calling out: “bruder! bruder!”

Bruder! Eat a dish of shit.

2025, Berlin

Who the hell are you, anyway?

— And the end. You have one sentence to sell yourself to the reader. Who do you consider yourself to be? Who are you?

— I remember Detsl had this line in the song “Who are you?”: “What have you done for hip-hop in your years?”… Man, to be honest, I don’t know. I only recently rediscovered myself as, like, a poet—rediscovered, if you count the fact that as a teenager I also wrote profane little poems. I’m bored, really; there’s nothing to read, no one writes anything meaningful about our generation, about the 90s, about the provinces, about people who got obsessed with activism and then were forced to skip the country and start a new life here in “Europka”—no one writes anything honest or powerful about that, so I have to—I’m trying. Literature is hard labor, actually, but what else is there to do—one has to live for some reason.