Gleb left Belarus for Ukraine because of repressions. In Kyiv, the guy first learned the feeling of home (and it’s not about missing Belarus) and stayed to help Ukrainians when a full-scale war broke out.

“Not Today, Not Yesterday, Not Tomorrow” talked to Gleb about “hunting” for food for pensioners, trips to Bucha, as well as about small joys during the war (and why it is not shameful).

Gleb, 47 years old

“In the bomb shelter there were children, people in wheelchairs, people with animals…”

I confess that in the 90s I voted for Lukashenko. In the first round I chose Shushkevich, but in the second round there was only one opponent-Kebich. I was young and naive, I thought I was choosing the lesser of two evils. It just seemed at that time that it would not last more than five years – after all, we are “almost in democracy and striving for democracy”. It was a mistake. And I directed all my civic activity in 2020 to correct it. I wanted a normal country for us and the future generation: I took part in marches, rallies, organised pickets, and ran away from OMON. After the events of 2020, I had to leave for Ukraine, where I received the status of additional protection because of possible repressions.

I met the war in Kyiv. At first everyone hid in a shelter, but on the third day it became difficult to sit idle. Then we gathered with our neighbours and discussed what to do. I decided to help with my own hands and in the first days of the full-scale invasion I dug sand and helped build barricades.

At the beginning of the war, I went down to the bomb shelter. I remember the first night there were about 200 people there. Among them were children, people in wheelchairs, people with animals. Residents of Ukraine were divided into two camps: some were leaving (I, by the way, argued with my Belarusian friends about it), and some wanted to help. And when the borders with Europe were opened, I decided to stay: first of all, because women with children, elderly people and those with health problems should leave first. The second reason is my documents. I am very grateful to the Ukrainian authorities for the speed of obtaining “refugee status”: some acquaintances from Belarus are still waiting for the status, their documents are being considered in the Department of Migration Service for 5-9 years. I was given all the necessary papers within a few months.

But most importantly, a volunteer mission

Every morning I went down to the shelter where the residents of the neighbourhood were hiding. There were many elderly people among them. They were afraid to go outside, and I brought them food (on the fourth day, any explosions and sirens became routine). Everyone said “Gleb went hunting” – no one knew what stores would open. Somewhere buckwheat was brought in, somewhere you could get milk, and somewhere, if you were lucky, and eggs. I collected orders every morning and went “hunting” in stores and pharmacies – it turned out to be such a courier service.

It was shameful to take money for food: these were elderly people, and in Kyiv the pension was quite small. When they asked me on my return from “hunting” how much they owed me, I said, “I bought eggs for (conventional) 20 hryvnias. And they told me: “not true, they could not cost 20” …. so two months passed.

“It was as if I had experienced clinical death…”

And then I caught a cold and stopped going down to the shelter so as not to infect anyone. Yeah, me and my dog learned the two-wall rule.

It’s hard to scare me, but the scariest thing was here in Kyiv. Last October, a shahed was shot down right above my entryway. It was like this: I hear a “balalaika-benz saw” (the shape of the drone is similar to a balalaika, and the sound of the flight – on a chainsaw), then – a flash, and suddenly the whole yard at night is sharply coloured in orange. Everything shook, and in a fraction of a second the fragments of the downed shahed scattered. Then the news showed the neighbouring district: the shrapnel hit the cars, some houses had their windows blown out, and not a single window was left in a college not far away. This is how fear disappears: now I am like a person who has experienced clinical death.

Sometimes I had to work (I’m a PR person) during a complete blackout: no light or electricity. It happens, you need to hand in a report urgently. Then you run to “indestructibility” points. These are tents where you can warm yourself and charge your equipment. And you can’t not work: foreign clients don’t realise that you have no light – they have deadlines.

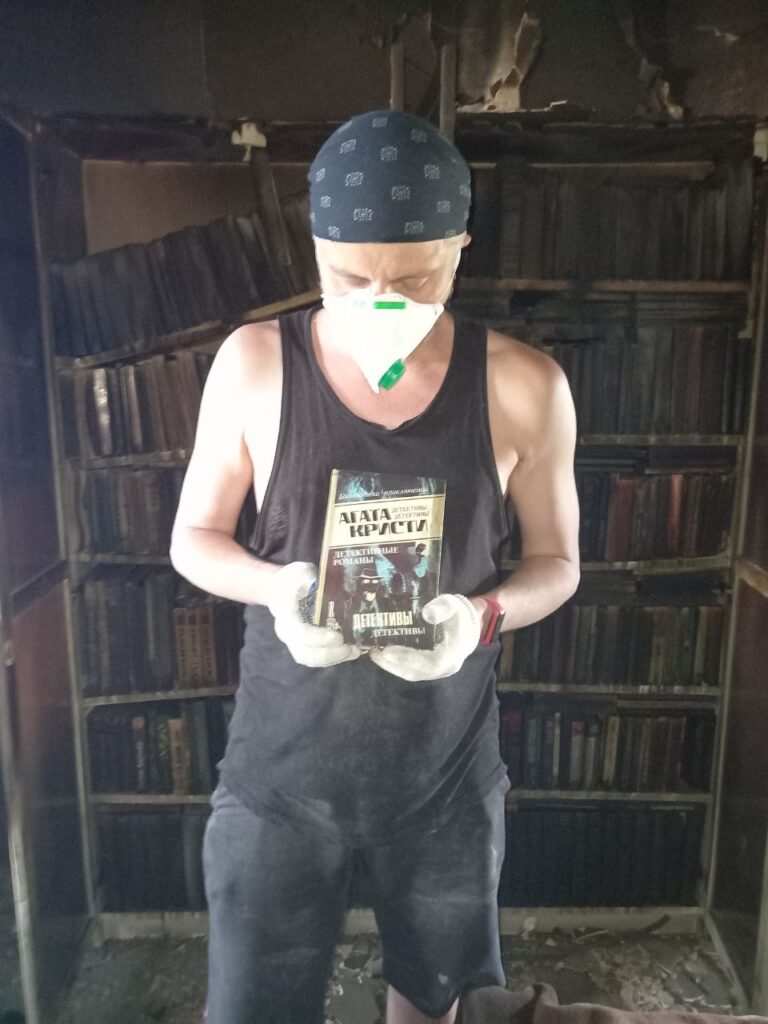

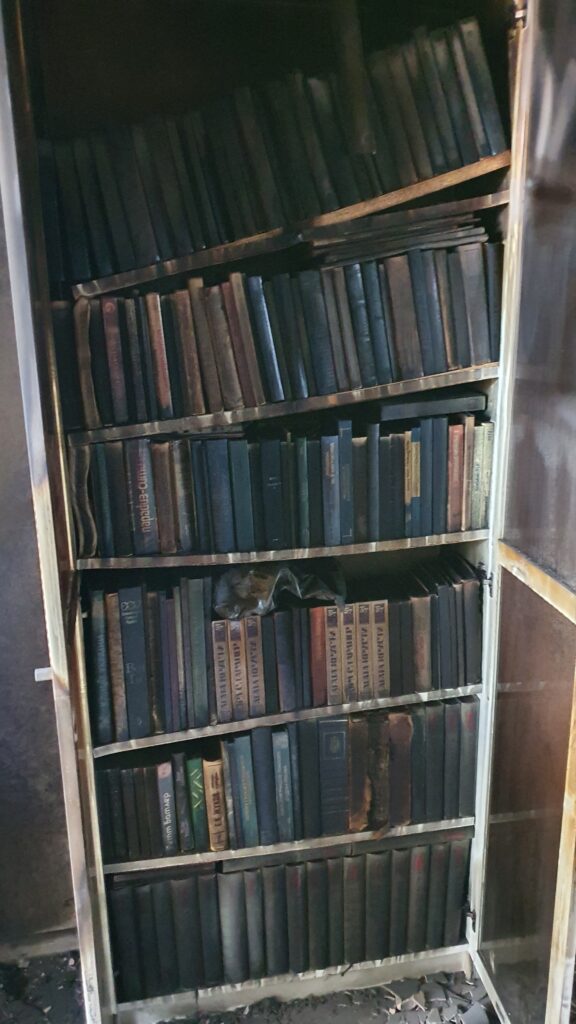

In April 2022, I met Karina, a volunteer from Belarus. She was helping Ukrainians and Ukrainian women in Bucha. After the liberation of the city, I joined her, and we started to gather there every weekend (and sometimes on weekdays) to remove rubble and ruins.

Of course, it was morally difficult for the residents of the destroyed houses to participate in the reconstruction – it is an additional mental trauma. And I understand them: I wouldn’t want to see my house after my arrival. That’s why we, Belarusian volunteers, were very much needed there.

By the way, not a single Ukrainian said anything bad about the Belarusians in Bucha – we were doing one thing.

Once, however, we had to face the notorious “why aren’t you in Belarus, why don’t you stop missiles with your hands?”. But it is clear that at home we would be arrested at once, and most likely right at the border. But here, in Ukraine, I can be useful.

I hardly communicate with my relatives. And here’s why: two years ago I called my aunt (it was our last conversation) during an air raid, and it was as if she didn’t hear it. By the way, later I asked a friend from Odessa on the phone “Do you hear the sirens howling? Maybe they are silenced?” – “Yes, I can hear everything perfectly well”. In short, my relatives take the position “I’m in the house, I don’t hear anything, I don’t see anything – so it doesn’t exist”.

At this stage our main task is to restore our reputation.

On the Independence Day of Belarus we organised a free distribution of potato pancakes in Shevchenko Park with the diaspora. The potatoes were grated by Ukrainians, cooked and distributed by Belarusians, and the place was offered by Kazakhs. Everyone was friendly, and not a single Ukrainian came up to us with his “go the hell home”.

I remember once sitting in the kitchen with a Ukrainian friend who also likes travelling. He confessed that he misses home a lot when travelling. Unfortunately, when I lived in Belarus, it was incomprehensible to me how one could not get depressed on the last day of being in Barcelona, Prague or Berlin before returning. By the way, I had to work in Russia for a while before 2014, but it was uncomfortable there. Especially after the whole “Krymnash” thing. It was as if this country had ceased to exist for me. Ukraine turned out to be more comfortable, despite the war. I realised: this is mine.

Once I visited Odessa, and although everything was just fine, on the third day I missed my Kyiv apartment. I finally realised what it was like to want to return to my home.

And then there was burnout. And that’s normal, because you can’t live in a post-apocalyptic show for three years.

Any loud sound: a truck passing, something falling somewhere, and I’m already glitching that we’re being shelled. I started to receive free psychotherapy, went to several psychotherapists. One therapist gave great advice about small joys. You woke up, petted the cat – already positive. The dog came to you – again a moment of joy.

For this joy, you do not need to punish yourself. Once on an excursion in the new cool interactive museum of the “formation of the Ukrainian nation” the guide noted that the military say: “we are fighting, not so that you do not worry about us, but so that you live well”. Not in the sense that you should dance, drink and have fun during the war, but that we (the rear of volunteers, civil activists) should hold on no matter what.

I go to the cinema (strangely enough, the cinema works), I like to swim, I play sports, and I’m waiting for spring to train in the open air. Also, my dog got a friend and her owner calls us to the dacha all the time. Thus, something like a family circle has appeared.

From the other burnout-fighting life hacks – informational detox. Lately I’ve been reading, literally, a few reliable channels, everything else is unnecessary noise.

Lastly, I would like to say that in this whole story, Belarus has unfortunately given territory to the enemy. To some extent, we will be held responsible. To the sceptics I suggest to watch the movie “The Nuremberg Trials” of 1961 (I myself, by the way, watched it a year ago). At the beginning of the movie there is a quote: “We didn’t know anything, we couldn’t do anything”. In our case it won’t work. That is why, as a Belarusian, and, at the same time, a person who lives in Ukraine, I am doing everything in my power to bring the victory closer.

This article was created as part of the Free Belarus Center scholarship program